Using a wrong term

Partnership is one of the most overused terms in business and particularly when discussing supply chains. The dictionary meaning of the word is a sharing of risk and reward. Do any of your organisation’s relationships with suppliers match the meaning? The more familiar approach for buyers is you take the risk and I take the reward.

This approach has been highlighted at one of six government initiated inquiries in Australia concerning how supermarket chains deal with their suppliers and consumers. Over the years, major economic sectors in Australia have become duopolies, where a few companies dominate. For supermarkets, two companies control about 65 percent of the national food market. In comparison, the largest supermarket in the UK has a 28 percent market share, in the US, 25 percent and in China, the top five supermarkets have 38 percent.

In Australia, there is competition at the supermarket checkout, due to ‘specials’, coupons and ‘bulk buys’. However, the margins posted for the dominant supermarkets in Australia are twice those experienced in Europe and the US. To maintain high margins in this duopoly market, the major supermarkets use their buying power on suppliers.

Even though suppliers are called ‘partners’, and the relationship a ‘partnership’, the inquiry is reported to have identified that supermarkets maintain their margins because suppliers must accept the risks in contracts. In addition to requiring a low buy price (and for fresh produce, only negotiate when the crop is available, so the supplier is a price taker), there are: not providing indicative quantities in the contract, with actual quantities required only identified when the purchase order is issued; rebates paid to supermarkets to ‘share’ price increases; long payment terms to provide working capital for supermarkets; suppliers to fund promotions and pay for advertisements in ‘free’ magazines for consumers and suppliers charged for damage to stock when it is at supermarkets. This is not a sharing of risk and reward.

Power in an organisation

While this example concerns supermarkets, the situation of some suppliers having to accept the risks in a business relationship is similar across industries. It is due to the unequal use of Power in a business relationship. Similarly, a supplier can use Power, so that buyers must accept some or all risks.

Power exists where a party in a business relationship can influence another party ‘to do things they otherwise would not do’. In business, Power and increased value (profit) accrue to organisations which possess one or more attributes that enable them to be considered as indispensable within a supply chain.

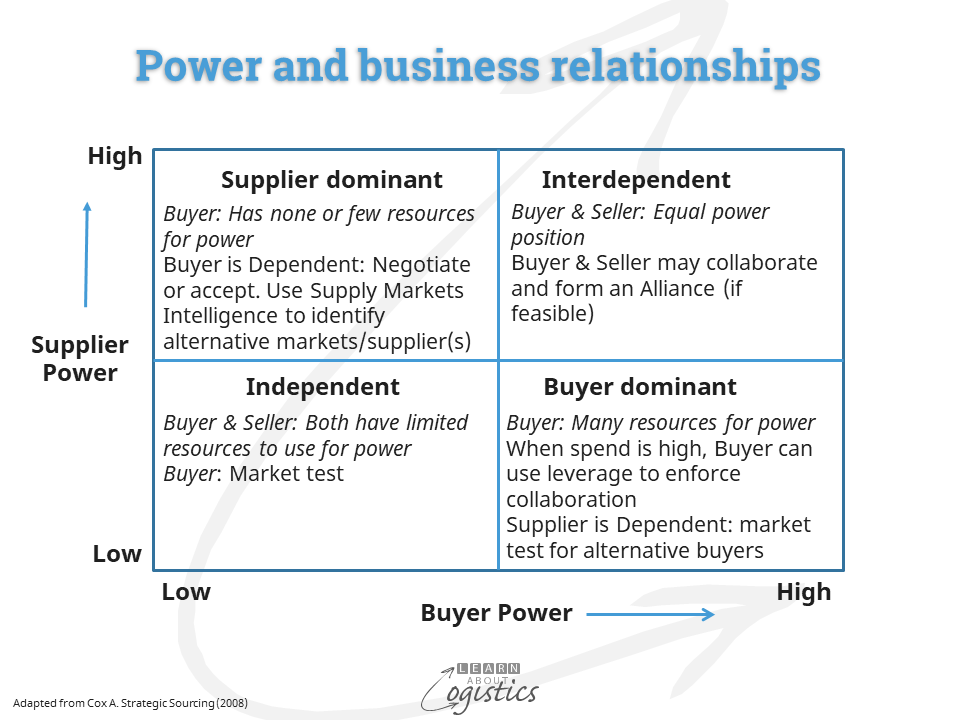

Andrew Cox noted in his book Power Regimes (2000) that buyers and suppliers are brought together because they have mutual interests. Each party is able to offer something the other needs, in exchange for something in return. However, their Power (or strengths) are not necessarily equivalent. Cox notes that “In order to achieve their objectives, each party needs to influence or even control the other’s behaviour. Their ability to do so will depend on the ability of each party to grant, hinder or deny the other, relative to the perceived ability for the other to do the same”. This ability is governed by the relative utility (or usefulness) and scarcity of the resources (or factors) that each party is able to present, as shown in the diagram.

The diagram indicates four options within a buyer-seller negotiation situation. It is obviously better to be dominant rather then dependent with both suppliers and customers, because dominance enables more flexibility for the business.

In a buying situation, the use of Power occurs where an organisation:

- Owns a supplier (or has a controlling shareholding)

- Controls the range of decisions a supplier can make

- Exerts considerable influence over a supplier to secure a more advantageous contract

A buyer is able to exert influence over a supplier through:

- Emphasising the organisation’s buying volume in a supply market

- Promoting the buying organisation’s likely predictability of future purchases

- Identify Limited alternative buyers in the market

- Have Knowledge of the supply market and supplier’s costs

- Exploit the supplier’s dependency on the buying organisation or the Supply Chain

- Leverage (promote) the organisation’s brand, reputation, recognition and prestige

A supplier can also exert an influence over buyers through the following tactics:

- Barriers to entry into a supply industry, that limits supply of an item

- Licence from a government for suppliers to operate or obtain critical materials

- Ownership or control of capabilities at a Node and Link in a supply chain, including capacity, specialised knowledge and technology

- Limited substitutes available in the supply market

- Cost to switch supplier when specialist assets must be accessed

- Complex product – incorporate value added services into the product, which cannot be easily duplicated

- ‘First mover’ advantage for new products

- R&D – provide a flow of new products and services that address customer needs

- Technology leadership through patents, copyright and intellectual property (IP)

- Reputation and prestige – perceived as the ‘best’ supplier for a product or service

- Spread of customers – the supplier reduces their dependency on large and powerful buyers; some organisations impose a low percentage of total sales that can be conducted with any one customer

Business relationships

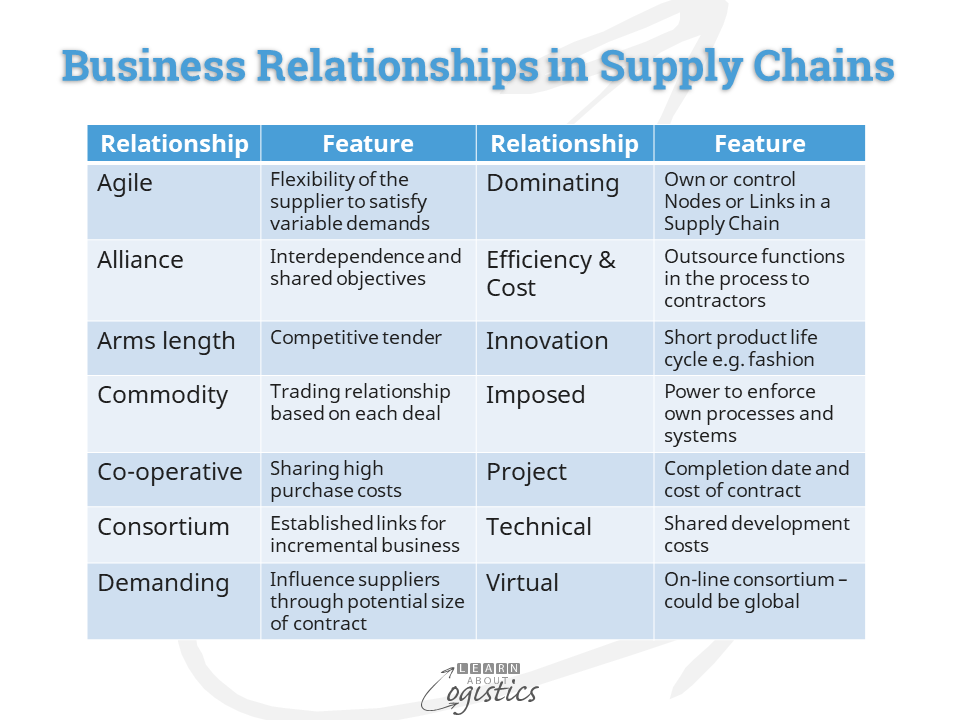

In addition to this list (plus others) of potential negotiating levers, are the external influences (of supplier’s suppliers) that can affect relationships with your organisation’s suppliers. The result will be a range of relationships that must be understood and managed to avoid or reduce unpleasant surprises. The diagram below identifies some types of relationships. Note that ‘partnership’ is not included; instead the more appropriate term of Alliance is used for two entities that have Interdependence through relatively equal Power and therefore the potential for collaboration (see the diagram above).

The types of relationships need to be understood for their benefits and limitations, then incorporated into the Supply Chains Network Design Map. This adds to the usefulness of the Map to provide a model of how relationships in the supply chains should be managed to achieve particular outcomes. However, a desired level of co-ordination between companies at Nodes and Links in your organisation’s supply chains is unlikely to be achieved, because the use of Power by parties in the chain will not provide a balanced flow of value and items to the end users.