Unsustainable future

The world is consuming the planet’s resources 1.7 times faster than it can regenerate. In anyone’s language, this is both a continuing challenge and unsustainable. Change is therefore required to economies, businesses and the lifestyle of people in developed countries. But how difficult will this be?

Between 1970 and 2020, the population of the USA increased by about 60 percent. However, consumer spending increased over the same period by about 400 percent (adjusted for inflation). The figures are similar for other developed countries and all are unsustainable. Yet, the governments of these same countries are hoping that their citizens will help economic recovery from the pandemic by opening their wallets and spending on ‘stuff’ – shopping as a positive act!

For a sustainable future requires a reduction in the use of resources by 40% (more in developed countries), which means a different attitude to making, selling and using consumer products. Companies will need to undertake Scenario Planning exercises to identify the effects.

For example, governments could impose price signals to reduce demand, such as VAT/GST rate increase, a; tax on non-renewable materials in an item, fuel tax increase and road usage charges.

The behaviour change required would, for example, be: less buying of ‘stuff’ (especially apparel), buying fewer but better quality clothes, reduced usage of utilities, less travel (especially business). white and brown goods (for kitchen and lounge) have durability labels and must be repairable, with branded parts at reasonable prices.

Examples of suppliers close to customers are: additive (3D printing) manufacturing; small automated ‘packaged’ production systems e.g. current ‘hot bread’ shops; cake and tart making, coffee roasting and packaging, knitting machines for ‘while you wait’ manufacture.

What happens to supply chains?

If economies will be challenged to change, then businesses also have a similar challenge, increased because of timing to coincide with changing customer expectations. Conceptualising a new style of business and its supply chains will be the barrier for businesses in the transition to a low, then zero carbon economy.

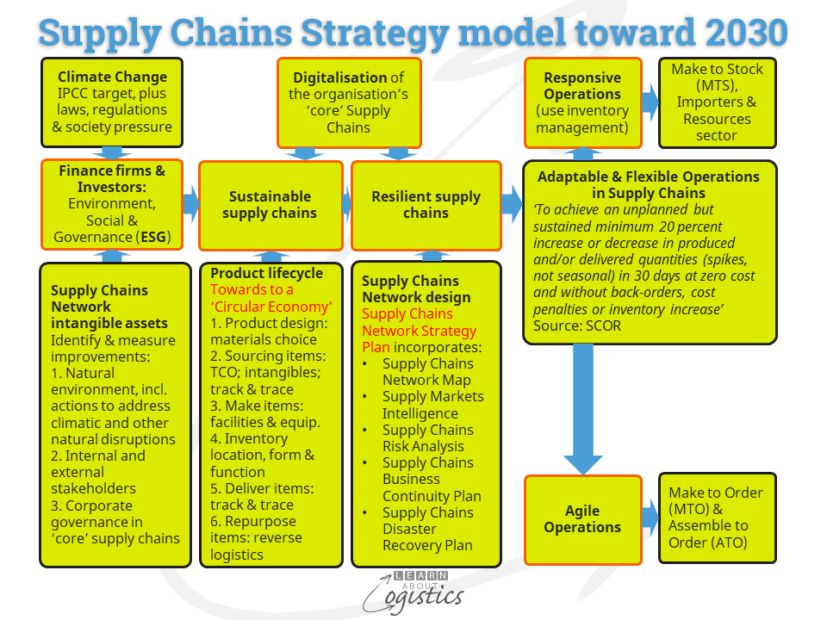

A previous blogpost discussed the demand from financial firms and shareholders for disclosure by companies of the aims and objectives concerning Environment, Social and Governance (ESG). This is the responsibility of an organisation’s Board of Directors and CEO. Structuring an ESG report can be based on guidelines, such as the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) and the Science Based Targets Initiative (SBTi). Within a few years, the ESG report will likely be a document presented to shareholders with the annual financial report.

As discussed in that blogpost, the strategic direction of an organisation’s Supply Chains will be a major part of a ESG report. The strategic direction will inform the Supply Chains Network strategic plan and its implementation is the responsibility of operational managers in the Supply Chains group – Procurement, Operations Planning and Logistics.

As shown in the diagram, Sustainable and Resilient supply chains are designed and developed based on the ESG aims and objectives for intangible asset. From various dictionaries, the word Sustainable means: to nourish or keep alive; able to be maintained and continued; harvesting or using a resource so that the resource is not depleted or permanently damaged and conserving an ecological balance.

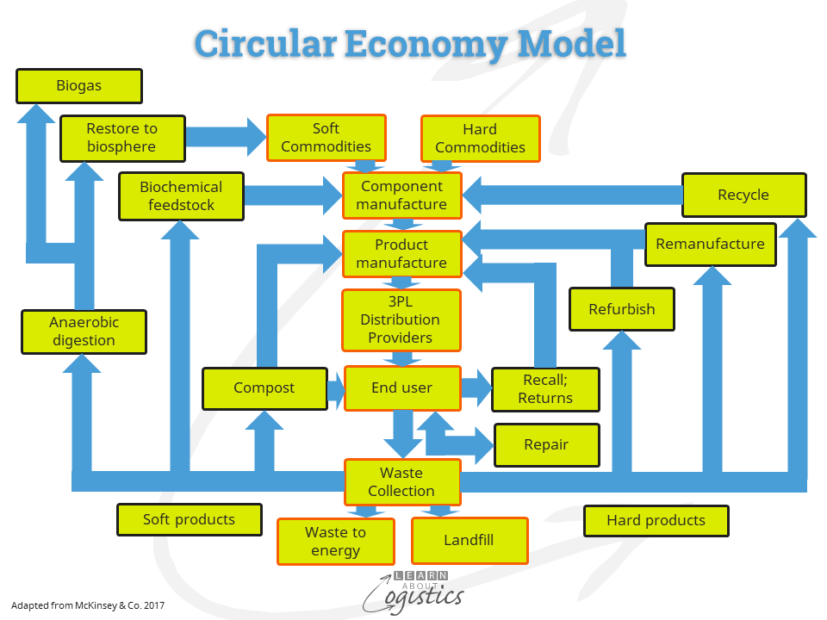

To meet these objectives requires that eventually (and preferably by 2030), your organisation (and all others) replace the current (and common) business approach of ‘take, make and dispose’, with ‘restore’. For process industries this means ‘re-use’ and for discrete industries, ‘design for re-use’, enabling multiple cycles of disassembly and a ‘right to repair’ by consumers. This is a ‘Circular Economy’

Sustainability in Supply Chains

In a Circular Economy, process (or soft) products are repurposed through an organic or non-toxic process. Discrete (or hard) products are not disposed, but re-purposed, as shown in the above diagram. This process is called Reverse Logistics and contains words that commence with ‘re’. Products within the groups called ‘recall; returns’ and repair will be ‘made good’ and returned to the customer as repaired or within warranty. If considered as unfit for use, then together with products that are at their ‘end of commercial life’, will be assessed for refurbishment or re-manufacturing (i.e. reusing parts that meet quality standards) at a dedicated location(s).

The product is then returned to market with additional ‘re’ activities of repackaging, relabelling, restocking and reselling. The result is that the total cost of Reverse Logistics is substantially more than the cost of the initial Forward Logistics.

If refurbishment and re-manufacturing are widely adopted by industries (or are required by government legislation), then markets could change for these products from ‘consumers who buy’ to ‘users who rent’. This would influence changes to the structure of supply chains that incorporate multiple cycles for products and where Reverse Logistics becomes a major feature.

When implementing extensive changes to supply chains, a factor to consider is the inter-connections between suppliers. How events at one or more supplier or industry can affect demand and supply factors in industry sectors that are suppliers to your tier 1 suppliers. All interruptions can be without your organisation’s knowledge or control. These are the emergent results of a ‘complex adaptive system’, which is the description of a Supply Chains Network.

Power in organisations

Substantial changes will only gain traction when people believe that the future of a business is under threat and the factors identified for long term viability are strategic to the business and to their jobs. Action taken can then be influenced by factors of Power in your organisation and the influence that people may exert when using it.

Exercising Power in business relationships is ‘the capacity or ability to direct or influence the behaviour of others or the course of events’. An organisation chart does not reflect the use of Power in an organisation. Instead, it is built through such factors as: standard operating procedures, performance management processes, remuneration models and the geographic locations of administration and operations. Threats to any assumed power in an organisation will be met with resistance by those who could lose power in a re-organisation. This is accentuated when the proposed changes are generated by the imposition of ESG from forces outside the organisation.

Only when a change has endured past the tenure of executives and managers at all levels who participated in the change (and their successors), can the change be called Sustainable. Therefore, the success of substantial changes that may be required, as ESG directives are proposed and implemented, will require the underlying structure of Power to be challenged and changed. Supply Cain professionals be warned!