Growth for container shipping lines.

International container shipping is an undifferentiated industry – a container is a container and the ships are very similar. To grow their individual businesses, options for shipping companies are to increase volume, reduce unit cost or to construct a vertically integrated business. But what could be the effect on customers’ supply chains?

To achieve their business objective, two popular choices are Mergers and Acquisition (M&A) between companies in the industry and takeovers of upstream and/or downstream businesses. The M&A activity of larger shipping company’s has resulted in major international trade routes now controlled by a few companies and alliances.

To illustrate this situation, the 10 largest container shipping companies in 2009 controlled about 58 percent of container traffic on the world’s major routes; by 2015 the top 10 market share has risen to about 64 percent. In 2018, the top 10 container shipping companies (less than 10 percent of companies in the business) had a market share of about 83 percent .

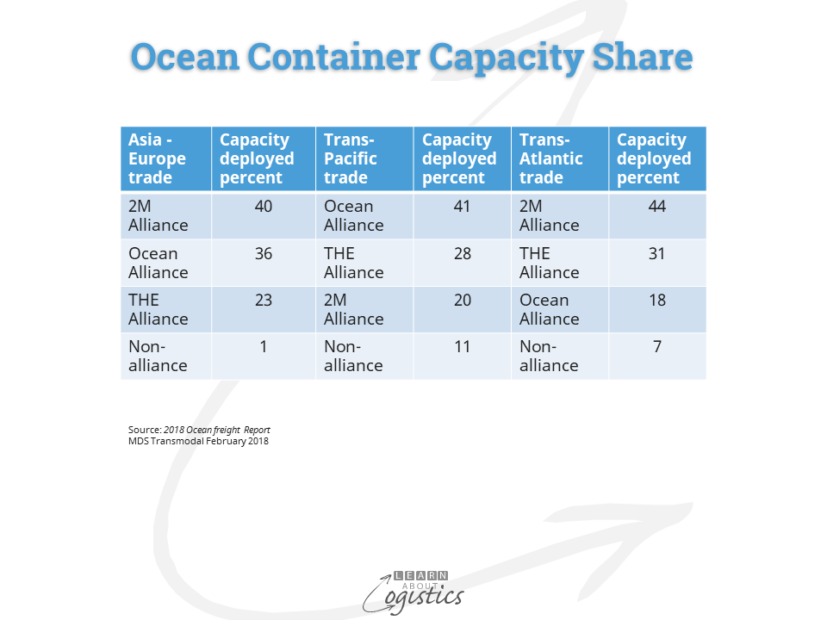

On the three major international trade routes, the potential increase in negotiating power for these alliance businesses is shown in the table:

Membership of the three alliances are:

2M Alliance:

- Maersk Line, including Hamburg Sud

- Mediterranean Shipping Line (MSC)

- HMM (Hyundi) – not officially in the alliance, but has a commercial relationship

Ocean Alliance:

- CMA CGM

- COSCO + Orient Overseas Container Lines (OOCL)

- Evergreen

THE Alliance:

- Hapag Lloyd

- Yang Ming Marine

- Ocean Network Express (ONE); the merged group of Mitsui OSK Lines + Kawasaki Kisen Kaisha + NYK Line

The commercial objective of the alliances is to better control capacity (and therefore freight rates and add-on loading’s) on each trade lane. This is achieved by improving the capacity utilisation of fleets, through the ability to change the mix of vessels in meeting market and tonnage requirements.

The range of vessels available is illustrated by Maersk Line, which has about 700 ships (owned and chartered) of between 20,000 TEU and 1,500 TEU. Currently, the largest ships are six OOCL vessels sailed on the Asia-Europe trade lane, each with a capacity of 21,413 TEU.

A scenario for container shipping is therefore:

- Asia – Europe trade lane operates the largest vessels

- North America: Channel water depths and upgrades to port infrastructure and materials handling capabilities dictate the vessel size for the trade:

- Transpacific trade lanes: post-Panamax vessels to about 16,000 TEU (at Long Beach, California) and 12,000 TEU at Ensenada, Mexico for the San Diego – Tijuana region

- Transatlantic trade lanes: ports range from post-Panamax of 6,000 TEU to about 12,000 TEU (at four ports)

- South Asia: Due to ports in the region having shallow depth, they are restricted to smaller container ships. The port of Colombo in Sri Lanka is currently the trans-shipment port of choice for the region, but Pakistan, India and Bangladesh have projects or plans underway for their own trans-shipment ports

- North-South routes to Oceania, Africa and South America use vessels of less than 8,000 TEU to service these smaller volume trades

- However, few ports on the north-south routes are equipped to handle 8,000 TEU ships. The emphasise is likely to focus on ‘hub’ ports – those that can handle 8,000 TEU and larger ships. Then trans-ship containers to other ports on smaller (<4,000 TEU) vessels, or inland by rail or road.

Research by MDS Transmodal Containership Databank, February 2018 indicate that the larger the shipping line, the easier it is to change the network of ships on offer. In the research period (Q1 2014 to Q1 2018), the number of services offered by alliances increased substantially, ships per service remained the same, average ship size increased by about 25 percent and round trip length in days was reduced. By providing more flexibility and adaptability to changing market conditions, smaller shipping companies are coming under increasing commercial pressure, which could continue to lessen competition.

Intra-region shipping container trade

Major regions and sub-regions in Europe and North America mainly use road and rail for intra-region transport. However, the Asian region is reliant on container shipping rather than land transport, for its intra-region trade due to the region’s geography and lack of investment in rail and road infrastructure.

Intra-Asia trade routes refers north to China, Korea and Japan, east to the Philippines, south to Indonesia and west to Myanmar This comprises the East Asia and South East Asia regions and is the world’s highest volume container shipping market.

This feature is maintained by the production of components in countries of the region. These ‘intermediate goods’ have final assembly in an Asian country before being shipped to international markets via the two major east–west trade lanes – the trans-Pacific and Asia–Europe.

The connection with major global trade routes has meant that in a competitive market and to gain global business, shipping companies have used pricing for intra-Asia routes as ‘loss leaders’ (pricing below cost to gain other profitable business).

However, this situation could change, with the formation in 2018 of an alliance comprising 14 shipping companies based in South Korea, called the Korea Shipping Partnership. This alliance will initially focus on operations in Southeast Asia, with the objective to address the demand-supply capacity imbalance on intra-Asia routes and therefore reduce operating costs.

While the combined capacity of the alliance is less than 25 percent of that provided by non-Korean shipping companies on intra-Asia routes, the initiative may well encourage other alliances to be formed.

Change and supply chain design

For some years, container shipping companies have been investing in port operations, to gain priority berthing, maintain dedicated berths and improve crane productivity. To extend this approach of vertical integration, some container shipping companies have taken a financial interest in freight forwarders. To offer additional ‘integrated’ logistics services such as container storage, customs clearance and inland transport would require shipping companies to make additional acquisitions.

The trend towards more control of container capacity, ‘hubs’ and shore-side activities by shipping alliances and large companies could eventually increase total transport costs for shippers and therefore influence supply chain design. Change could take another ten years, but as the trend has been occurring for the past ten years, it has a momentum. So, as a supply chain professional, when reviewing your organisation’s supply chains, consider a changing scenario for container shipping.