An acronym lives again

To explain how enterprise will structure and perform as the COVID-19 crisis recedes, a speaker at a recent on-line conference used the term VUCA, which required a dig into the archives.

The acronym was developed in the late 1980s by the US Army War College, in relation to strategic thinking in a post-Cold War scenario. While it was occasionally mentioned at conferences and in articles, the acronym did not catch the media’s attention and so it retained a low profile.

The VUCA approach to strategic thinking is based on four conditions:

- Volatility: The speed of change over a period of time, where situations are unexpected, the pattern of events is unstable and the duration is unknown

- Uncertainty: the potential for surprise and a lack of predictability concerning an event’s cause and effect. Uncertainty is heightened with increased flows of items, money, data and information. Risk analysis required

- Complexity: situations have many inter-connected parts, Constraints and Variables (with Variability), which can interact dependently, independently and inter-dependently, to affect outcomes and increase Uncertainty. The more complex the situation, the more difficult it is to analyse, given the volume of data and information available for decision making

- Ambiguity: The lack of clarity about how to interpret a situation, caused by vagueness about principles, terminology and definitions e.g. supply chains. This leads to misunderstandings, due to information being incomplete or inconsistent about the preparedness and responses to events

At the time when VUCA was developed, the term ‘supply chain management’ was becoming popular and misunderstood. Incorporating the term ‘management’ generated opinions that supply chains could be planned and controlled and therefore managed. Having a view of supply chains from within a VUCA scenario was not accepted.

Although developed to address corporate strategy, the VUCA approach has value for senior executives when considering an organisation’s supply network at a strategic level. An acceptance of VUCA can help to upgrade your organisation’s capability to:

- Identify potential situations that could affect the organisation

- Prepare for alternative realities and their challenges (such as the COVID-19 crisis)

- Appreciate the inter-dependencies of variables in the supply chains

- Recognise that decisions and actions have consequences, which could be unintended

- Consider the possible opportunities for your organisation as an outcome from negative events

Uncertainty and the location of facilities

Are products produced and warehoused in appropriate locations to provide the expected customer service, but which reduces the levels of risk? This aspect of supply chains was researched, developed and discussed some thirty years ago. With the challenges generated through the current crisis, it has returned.

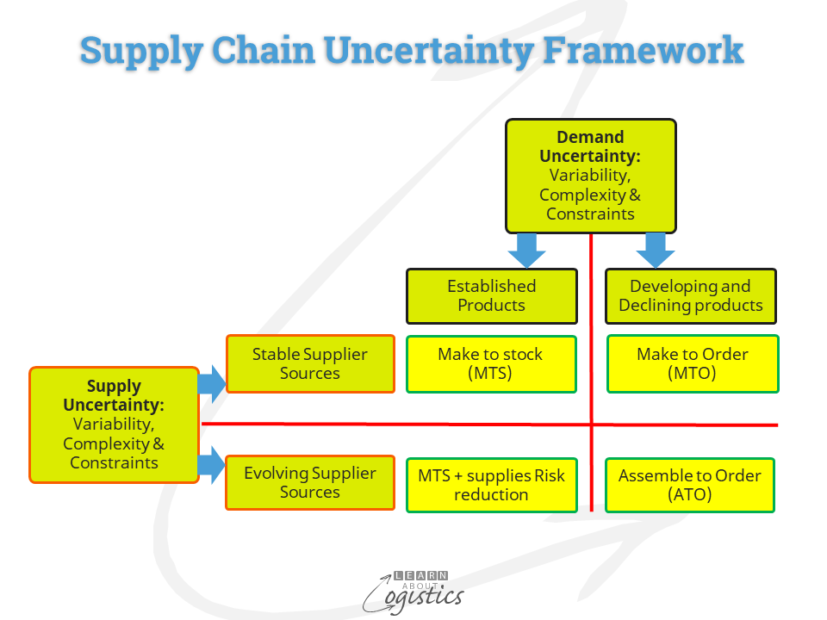

Businesses rarely have products with similar Demand and Supply Uncertainties. Established products may not have Stable supply processes e.g. food products with stable demand rely on produce supply which is dependent on weather and disease. Developing products can have stable supply e.g. fashion products have uncertain demand, but the supply base is mature and stable.

- Make to Stock (MTS) justification is: economies of scale; throughput and yield (number of units produced from the inputs) and integrated operations using optimisation techniques. With a more predictable business structure, techniques can be such as: Vendor Managed Inventory (VMI) and Lead Logistics Provider (LLP). MTS builds inventory to satisfy the forecasts of sales, but inventory reduces the flexibility of an organisation when responding to market changes.

- Make to Stock with supplies Risk reduction. To reduce Risk, an objective is to ‘pool’ and share input resources and the subsequent risks e.g. dual sourcing, sharing material safety stocks and joint contracts for increased transport utilisation

- Make to Order (MTO) provides a design and manufacture service, enabling options to be applied to a base product – it is the adaptation of pre-designed products. The base item could be produced in advance of orders, depending on:

- the expected (by customers) delivery lead time for finished items

- the variability of demand for the base item

- the inventory value of the base item

- the range and complexity of options

- Assemble to Order (ATO) applies to both discrete and ‘mix and stir’ (non-discrete process) materials assembled to order. The specific orders for catalogue or recipe products are received by Operations Planning from customers or the sales department. An ATO business will make or buy materials, components, sub-assemblies, packaging and options to assemble and deliver products produced from both directly purchased and previously produced parts and stocked discrete sub-assemblies or ‘mix and stir’ formulas or recipes.

Both MTO and ATO utilise ‘Form Postponement’ or ‘Delayed Configuration’, of product lines that have a common platform of modules, components and materials. The product customisation or final assembly occurs when the customer requirement and/or market destination is known.

The metric for measuring flexibility and adaptability in MTO and ATO Supply Chains to provide Availability (the role of Logistics) can be:

“To achieve an unplanned but sustained minimum of 20 percent increase or decrease in produced and delivered quantities (spikes, not seasonal) in 30 days at zero cost and without back-orders, cost penalties or inventory increase” (adapted from Supply Chain Operations Reference (SCOR).

Location for product groups

- Make to Stock with Stable, more predictable demand – Asia based factories for global distribution, with established supplier industries and supply chains. This is excepting where domestic availability of raw materials e.g. food processing, makes domestic MTS strategies viable.

- Less predictable demand requires domestic factories based on MTO or ATO processes that are responsive to customers’ needs

- MTO and ATO will be assisted by the development of manufacturing automation technologies and associated software. These can facilitate low volume production of multiple (but similar) products i.e. economies of scope, rather than economies of scale.

- MTO and ATO can import some of their inputs from other countries in a region as ‘intermediate goods’

- MTS inventories (cycle plus safety stock) are stocked in consumer countries; SKUs are picked and consolidated with MTO and ATO items for delivery against customer orders

Although some commentators are mentioning “the end of globalisation”, the crisis does provide an opportunity for businesses to review and adjust their supply chains to maintain customer service and profitability.