Reverse Logistics activities.

Reverse Logistics consists of the activities to bring items back from their current location, through the same or a different supply chain. It is therefore a cost; but, is that a negative for your enterprise, or a benefit which could produce a positive return? Do not view Reverse Logistics in a negative light; instead, consider all aspects that may assist your organisation.

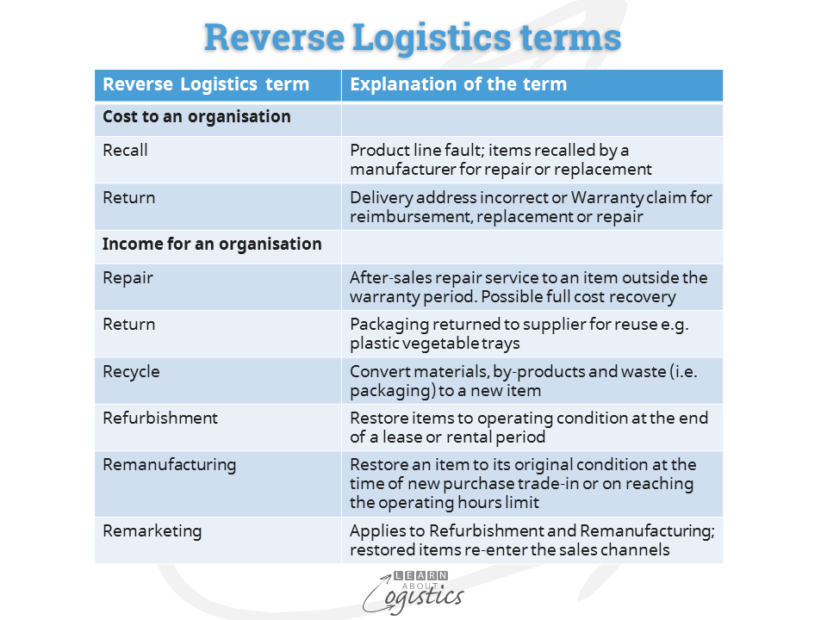

Reverse Logistics terms start with ‘re’. Identify the activities that will cost your organisation money and those which could provide a financial return.

The two Reverse Logistics activities that cost money are caused by errors in product design, manufacturing activities or Logistics. Recall of a product line may not occur very often, but when it does, the costs can be high. It involves (in quick time) identifying the item locations, organising the logistics activities for the recall, identifying whether items travel via retailers, dealers or distributors and then storage of the recalled items prior to decisions concerning rectification of the problem.

Return of a product due to an incorrect delivery address (or an associated factor, such as incorrect delivery acceptance hours) may fit a pattern or be ad-hoc. The cause(s) must be analysed and investigated, because if the underlying cause is not identified, costs could escalate. Product returns due to Warranty claims should also be analysed for patterns in relation to the cause.

Logistics processes for product Recall and Return need to be reviewed at regular intervals. If possible, conduct a mock exercise for product recall, due to the cross discipline involvement and understanding required by all involved about who is in charge and from where instructions will be initiated.

Reverse Logistics that provides income

For Repairs ‘out of Warranty’, the Logistics process will be the same as Warranty returns, except that the customer/consumer may be invoiced for the total cost of the repair.

After-sales product service for consumers is typically for home products, identified as ‘white goods’ (electrical goods used in the kitchen) or ‘brown goods’ (electronic and electrical goods used elsewhere in the house) and motor vehicles. Typically the product must be taken by the consumer to a repair centre, operated by the brand company or an authorised repairer. The time taken for repair can range from days to weeks, depending on where the service parts are located and the backlog of work is awaiting completion at the repair centre.

For industrial products, on-site servicing and repairs may be required. Depending on the urgency, repairs may be undertaken on any day and at any time. Planning for skilled technician availability and service parts location and availability is therefore critical.

The challenge for Logisticians is that many products are sold on global markets; however, a product sold in one country or region may not be sold in another. Service parts can be held across supply chains, at central DCs, regional warehouses and in service vans. Furthermore, products are usually under continuous improvement, so parts within a product model can change over time and can be manufactured by suppliers located throughout the world. Visibility and tracking of service parts is therefore critical. For inventory planning, there is a need to know how often parts fail (called the Mean Time Between Failure (MTBF)) and for what reason.

Returns can be profitable, when a commercial buyer works with suppliers to identify how protective packaging can be returned and re-used. If volumes are sufficient, the mode of transport will be in continuous use and therefore paid for. The savings are in packaging material costs.

Re-marketing is the term used for restoring items for further use; it is sub-divided into Refurbishment and Re-manufacturing. Items not owned by users (leased or hired) can be re-furbished to enable further use. Items owned by users can be re-manufactured to original condition and sold with a warranty. Both approaches require a Reverse Logistics process, managed as a profit centre.

Recycling is to convert materials, by-products and waste into new items. There is an old saying from the north of England which states ‘where there’s muck there’s money’ and this should be applied by Logistics to identify the items that can be profitably used in other forms and how to manage their movement and storage.

To illustrate the range of opportunities available, a recent article discussed Recycling at the Roermond, Netherlands paper mill of Smurfit Kappa. The mill now produces less than 1 kg of solid waste per tonne of finished paper, compared with competitors producing 32 kg. This is achieved by sharing waste streams with other businesses and customers.

Prior to focusing on Recycling. the mill sent 30,000 tonnes of wet disposals to the tip, costing 80 euros per tonne in fees. To substantially reduce that charge, the mill now:

- sells surplus bacteria globally and sulphur to local farmers for fertiliser after cleaning the river water

- uses lime sludge from the water as a raw material in paper-making. In the future, lime sludge, which is mostly composed of cellulose, could be used in polyethylene furanoate, or PEF, which is a bio-based alternative to PET bottles

- has developed fuel pellets from its plastic waste (after extracting harmful PVCs). 12 truckloads are produced per week for heating in lime kilns and cement works

- has customers for fine textile and hair waste, removed from recovered paper in the final screening; this includes a tulip grower who spreads it over his fields to prevent fertiliser run-off

The mill also uses waste streams of other companies in the area:

- calcium carbonate that a nearby toilet paper manufacturer produces as waste. They provide 12,000 tonnes per year, which replaces 6,000 tonnes of (more expensive) recovered paper at the paper mill

- starch waste from a nearby potato factory is used in the paper recipe

- a baby food manufacturer removes phosphoric acid from its products and provides it to the mill for use in the water treatment plant

- tomato stems provided by a local tomato grower to produce boxes, using 10 percent tomato stems

- the remaining 1 kg of solid waste per tonne of paper produced is mainly sand and glass, which could be used in the construction industry

This list of Recycling initiatives illustrates the value of a Reverse Logistics activity that effectively and efficiently organises the movement and storage of what previously is seen as a disposal cost. Together with the other profitable Reverse Logistics streams and management of costs, are there potentials for Reverse Logistics to be developed as an integral part of your organisation’s supply chains? If so, it is a first step towards Sustainable supply chains – but that is for another blog.