Review your supply chain performance measures.

Performance measurement at department level is often locally focused, without links to performance of the wider organisation or events outside the business.

My previous blog discussed ‘you behave how you are measured’ and noted that performance measurement can be debased. Managers (and their staff) can ‘tick the box’ while hiding behind what appears to be a comprehensive system of figures and statistical measurements. This is a breakdown of the linkage that should exist between the business plan, defined objectives and performance measurements.

Recent events have also illustrated that the best designed supply chain plans can be seriously affected by events – expected or unexpected.

- Germany: Historically, Germany has not been affected by extreme weather. However, 2017 contained the hottest October on record. The month also bought two major storms that severely disrupted the rail network and transport of goods (in some areas for weeks)

- UK: An IT component company was a supplier to a major IT business. The sales contract provided a large part of the company’s income. However, the customer did not renew the contract and the value of the company (its share price) fell, affecting all business and operational plans The company was sold to an offshore investor

- Australia: The country is on track to be the world’s largest exporter of gas. However a lack of rigour by the national government in the design of enabling legislation has resulted in domestic users of gas experiencing a shortage of gas supplies and higher prices than those paid by export gas customers. This has affected the operational plans of organisations reliant on gas

These examples emphasise that your supply chain performance measurement system must incorporate both internal operations factors and external factors that may affect or influence the supply chains. The external factors are identified under Business Sustainability and Business Continuity.

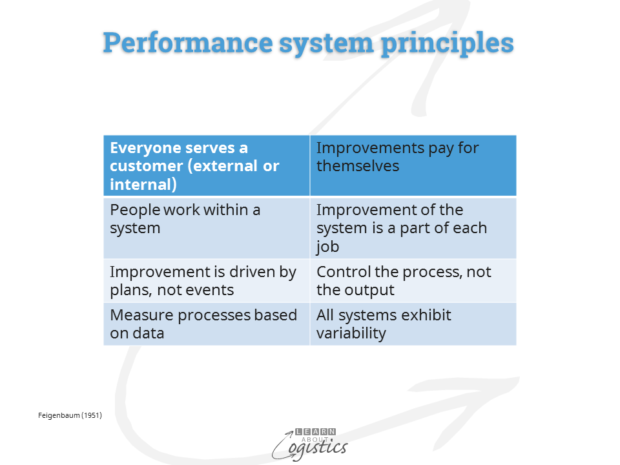

A viable performance measurement system requires a set of principles that all adhere to. A list of eight principles was published by Feigenbaum in 1951, when he was director of quality at General Electric (GE). These principles remain applicable in 2017 and can be read across each line in the table shown below.

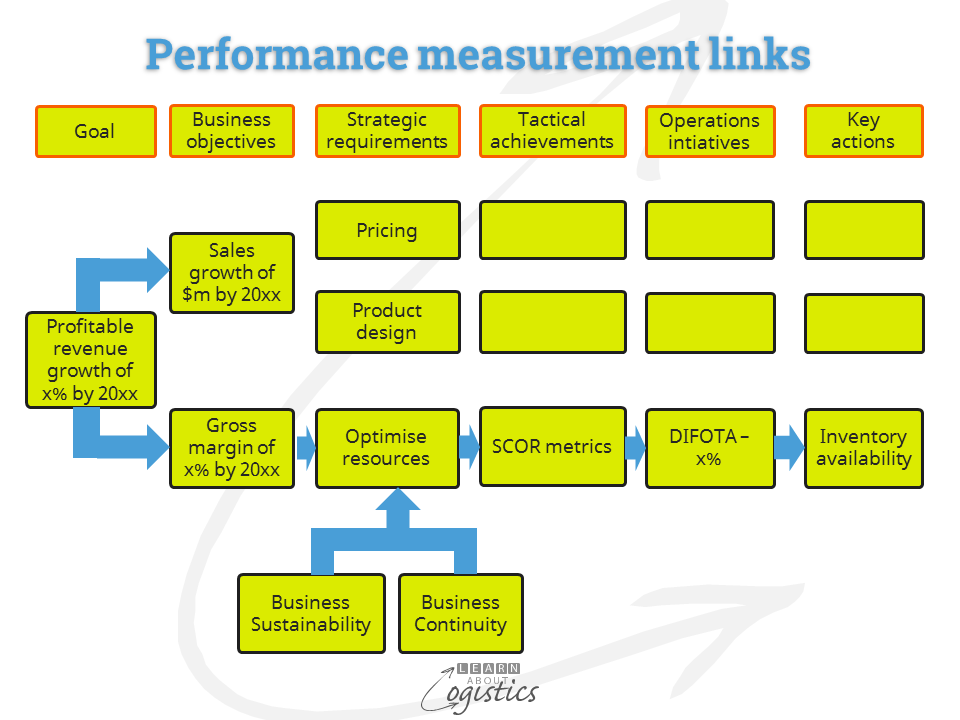

As stated in the table, ‘improvement is driven by plans, not events’. The performance measurement plan for your organisation is best structured as one plan. The diagram below is for a business in consumer packaged goods (CPG) or fast moving consumer goods (FMCG). This diagram shows the links between measures, which can be traced to the Goal and Business Objectives of an organisation.

The Goal of this business is to achieve a profitable revenue growth of ‘x’ percent by 20xx. Achieving this requires two business objectives:

- Sales of $m by 20xx

- Gross margin of ‘x’ percent by 20xx

Achieving additional sales will require its own range of strategic requirements. Obtaining a higher Gross Margin will require strategic requirements in the areas of pricing, product design and the optimisation of resources. To achieve the last factor requires effective supply chains, To ‘Optimise resources’ requires that the Gross Margin objective is structured as a number of ‘supply chain operations reference’ (SCOR) metrics. In turn, each of these metrics is linked with a ‘delivery in full, on time, with accuracy’ (DIFOTA) percentage that requires (for example) a measure of inventory availability. In addition to these measures of internal performance, must be measures relating to the external factors of Sustainability and Business Continuity.

Sustainability and Business Continuity

Sustainability is about more than the environment; it refers to the vulnerability of your business. This is underpinned by risk – what level of risk (and therefore added cost) will your organisation accept of a current situation before it changes behaviours (culture and strategy) to reduce the vulnerability. And your supply chains are where many of the risks reside:

- Procurement:

- buying items from suppliers in particular countries or regions

- the likelihood and consequences of man-made or natural disasters

- buying from suppliers in low cost countries (LCC) with added reputation risks (low wages, child labour, exploitation)

- Location of storage and distribution nodes in the supply network

- Reducing energy consumption and emissions through the supply network

- potential of regulated or price signalled increases in energy costs and reduction in emissions

- Minimising transport and distribution costs:

- Global politics can quickly change the transport (including fuel) pricing model

- Congestion costs and charges for road transport are likely to become a critical factor

- Transport and distribution costs can be reduced through improved collaboration along supply chains – how likely are customers and suppliers to embrace this concept?

Business Continuity (BC) is defined as the capability of an organisation to continue delivery of products or services at acceptable predefined levels following a disruptive incident. (ISO 22301:2012). This puts BC as a direct responsibility of supply chain professionals. If the supply network is a critical a part of your business as a shipper, or as a 3PL, supply networks are critical to your clients, then reducing BC risks is a strategic requirement.

The objective is to protect the interests of key stakeholders, the organisation’s reputation and brand and the value-creating activities. This last factor requires a process to identify potential threats to your organisation and the impacts to operations from the threats, to provide a framework for building the capability to effectively respond to the identified threats.

To do this requires that supply chain professionals:

- recognise that your supply network is a complex adaptive system, which can be affected or influenced by events outside your control

- define the supply network risks using a common vocabulary

- define and analyse scenarios that may reduce the risks

- be able to implement approved changes to the network and processes and

- measure the outcomes of changes, using a ‘one-plan’ approach to performance measurement, so that improvement programs are linked to strategic requirements

This blog has identified that a comprehensive approach to performance measurement is required, considering all aspects of your supply network. An approach that is an ad-hoc collection of tactical initiatives that address particular factors, will not be effective.