Improving flows through supply chains

The goal for professionals is to make Supply Chains more effective. However, the more typical focus for many years has been on making the functional silos within supply chains more efficient. That is improving the transactional processes within their silos.

The silo approach emphasises the implementation of three-letter acronym applications such as CRM, SRM, APS, WMS and TMS, often linked (or maybe ‘integrated’) within an ERP system from a single IT applications provider.

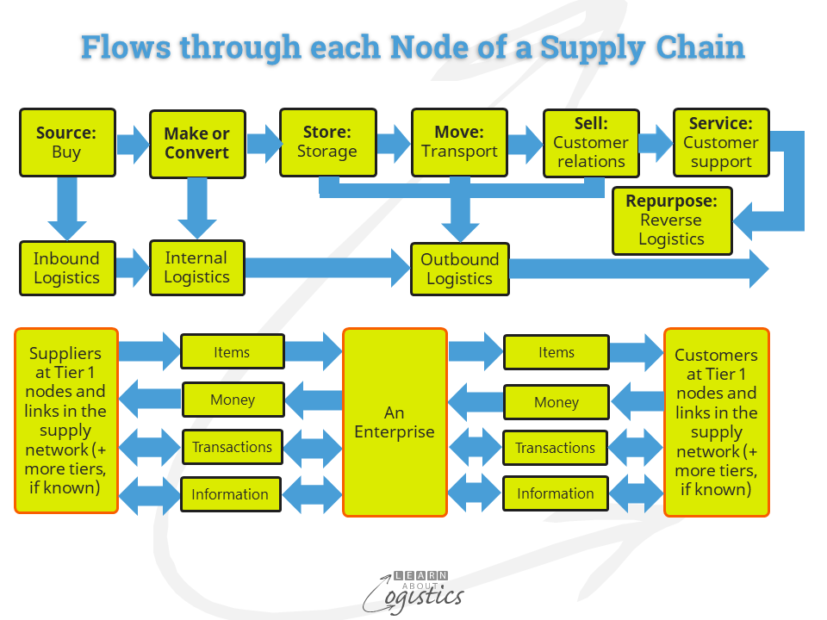

As discussed through its many blogposts, Learn About Logistics argues that Supply Chains have a much broader scope and influence on businesses than is often imagined and accepted. So, within the scope, the operating focus should be to improve effectiveness through the Flows of items, money, transactions and information between customers, the enterprise and suppliers.

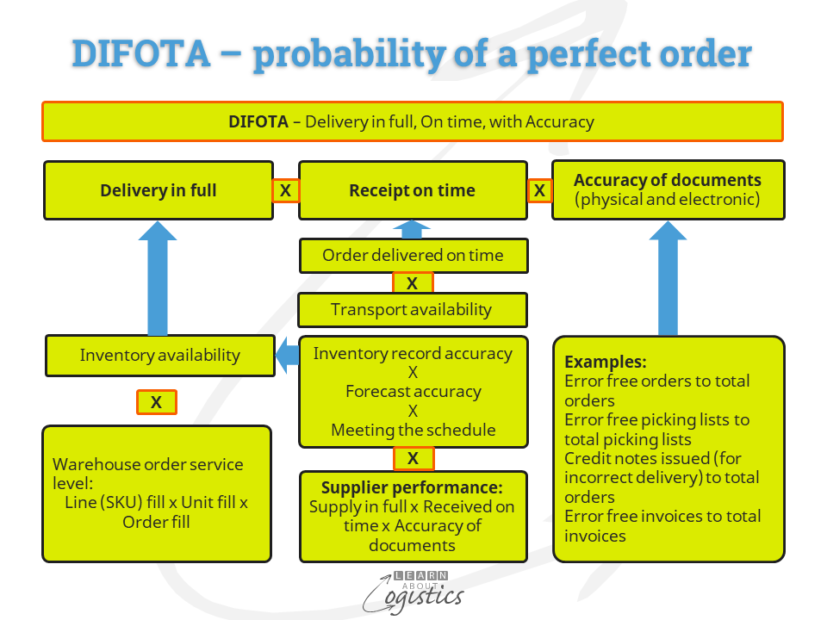

Flows commence with demands from customers, which connect and align each of the operating silos. Therefore it is preferable that the process of developing and responding to customer demand is not viewed as a functional process. Responding to customer demands is also not a single functional process; it requires the connection and alignment of the functions through management of the Flows. The diagram below illustrates how the measure of supply chains performance (Delivery in Full, On time, with Accuracy (DIFOTA)) is structured; relying on cross-function collaboration.

DIFOTA is one of three operational objectives for supply chains – the other two are: providing Availability for customers through the process of Sales & Operations Planning (S&OP) and minimising Uncertainty (risk) in an organisation’s supply chains. Note that the common feature of these objectives is that they are cross-functional in design.

Being a flexible organisation

Achieving the status of being an Agile organisation requires an understanding of the organisation’s Flows, which are identified through the Supply Network Design process. Again, this process is cross-functional, whereas relying on ERP systems will only provide functional efficiency, but not flexibility.

Becoming a flexible or Agile organisation is often identified by commentators as a worthy objective for a business, but usually without a definition of what that means.

Agility is defined within the Supply Chain Operations Reference (SCOR) model as: “The number of days to achieve an unplanned (that is a spike, not seasonality) and sustainable 20 percent increase in quantities delivered” or “The sustainable increase in quantities that can be achieved within 30 days at zero cost (back-orders, inventory or other cost penalties)”.

The blogpost Operations Planning in a changing demand market profile discusses aspects of Agility from the perspective of Operations Planning. Also, a discussion of Flexibility in organisation design is at the blogpost Flexibility in Logistics needs control of customer orders

Measuring performance in financial terms is critical for supply chains to receive sufficient attention as a discipline at the Board of Directors level. The free eBook Supply Chains Operating Performance – A Financial Approach to Measurement by Learn About Logistics, identifies four financial measurements:

- Supply Chains Working Capital

- ‘Cash to Cash’ cycle time

- Supply Chains Value Added (VA)

- Supply Chains Return on Invested Capital (SC-ROIC)

Although Supply Chains Working Capital and ‘Cash to Cash’ cycle time are the easiest measures to implement, a high level of performance in each of these measurements requires cross-functional co-operation and alignment.

So, to gain a understanding of your organisation’s supply chain performance requires the development and use of cross-functional processes and measurements that are underpinned by data and information concerning Flows. But what is the actual situation?

Supply Chain Applications

The table below lists Supply Network Analysis and Planning (SNAP) applications that sit above corporate ERP systems. Assuming the knowledge and capabilities the people tasked with implementing and using each application will take less time to implement than an ERP system.

These application contain the terms Analysis and Planning because this underpins supply chains and the three disciplines of Procurement, Operations Planning and Logistics. However, of the applications, which are cross-function and flow based? In column 1 (applies at corporate and global level) there is Scenario Planning, Risk Analysis and Supply Network Design. In column 2 (applies at region and country level) there is Global Trade Management Planning and Sales & Operations Planning. In column 3 (site specific) there are none.

Within businesses, there is plenty of planning – demand (or sales), distribution (including transport and warehouse), materials and supply, but the work is not connected. Planning is there to improve efficiency of the functional silo, not to make supply chains more effective.

As outsourcing of production and distribution has become a major component of some supply chains, the planning process for organisations is not just within the business, but should be based on knowledge of an organisation’s supply network. However, a supply network is a complex, non-linear but adaptive system, without central control. As demonstrated by current international actions concerning tariffs and non-tariff regulations, extended supply chains will adapt to new conditions and an organisation’s planning must respond and adapt, based on the best knowledge available.

In the future, your organisation is likely to implement more applications for use in the supply chain discipline or within functions that are supply chain aligned. However, as discussed, the applications are more likely to be developed on the basis of functional improvement, rather than supply chain effectiveness.

For professionals working in supply chains, their role in selecting planning applications is to initiate and promote the goal of improving supply chain effectiveness. When reviewing the capabilities of applications, planning staff will consider functionality and ease of use. However, based on the goal, professionals should consider:

- Fit of the application to the business/supply chains requirements

- Source(s) and confidence of the proposed inputs and the destination and use of the outcomes

- Potential for harmonising and synchronising the data across functional silos

- Alignment of Flows and processes across functions

- Capability of analytics in the application to assist planning and business decisions

It is strongly advised not to treat the purchase and implementation of software applications associated with supply chains as an IT project. Successful applications are likely to increasingly be viewed from the aspect of connectivity (but not ‘integration’), that assists Flows through the business and its supply chains.