Supply Chain talent skills and availability

Recently, there have been articles concerning the available talent for supply chains – both the desired skills and decreasing availability of people with the skill set for particular roles.

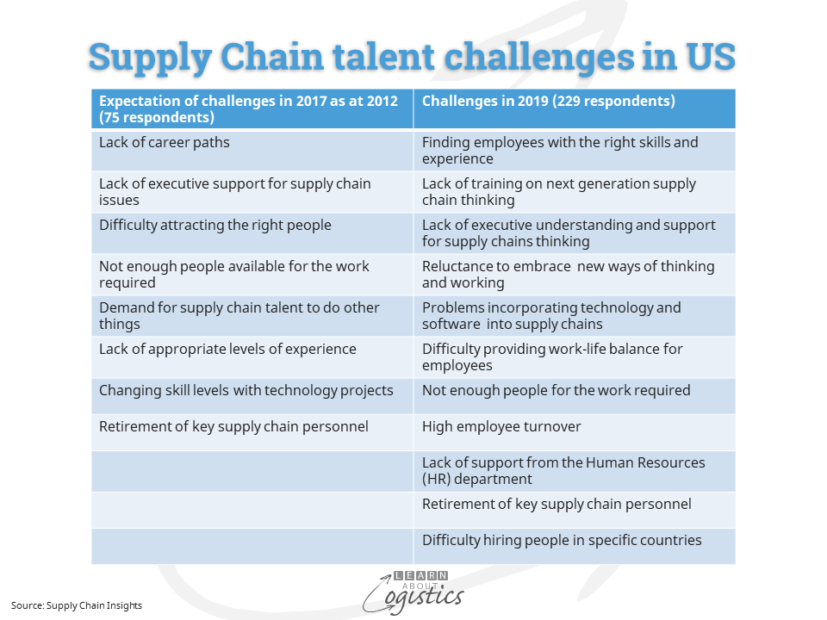

But this is not new; the situation has existed for some years and is likely to continue, because little has changed. For example, in November 2012 and September 2019, Supply Chain Insights reviewed the shortage of supply chain people across all supply chain roles in the US, under the title Supply Chain Talent. The ranking of results indicates that over this period, the challenges have been similar, with some remaining exactly the same:

In the 2019 review, it noted that not all job roles in the US were equally affected:

- Finding middle management in Supply Chain Planning is difficult

- Roles in customer service, procurement and transport are easier to fill

- Analytic skills are deficient. The cause is suggested to be that Supply Chain education programs in the US are typically embedded in the Department of Marketing within University Business Schools

- Middle management skill development should be considered separately from entry level recruitment, which is mainly based on academic achievement

- Not mentioned in the survey was the demand and supply situation for people with vocational training (Diploma and Certificate)

Other countries are likely to have different demand and supply situations for people in supply chain jobs. Therefore, while inputs from many sources can be useful for analysis, do not accept data from the US as being directly applicable in your country.

Influencing the availability of talent

There are three parties that influence the availability and skill of supply chain talent: individuals, education and training establishments and employers.

Individuals: The desire by young people to work in supply chain roles is dependent on the perception of these roles in the general community and within industry. For working people, the perceptions of the work roles and importance of jobs in supply chains can influence people to switch career paths. If perceptions provide a low demand for jobs, it influences the supply of relevant education and training courses.

Education and training establishments will not exert themselves without encouragement from industry that graduates will be employed and there are career paths. An additional challenge is where to locate cross-function supply chains teaching within vertically structured teaching departments? But, to have a separate supply chain department requires money, preferably from committed employers.

But, employers must be clear in their understanding the role of ‘how’ and ‘why’, which can be summarised as ‘Supply Chains are the environment in which Procurement, Operations Planning and Logistics operate’. For example, the factors associated with managing warehouse operations (the ‘how’) is within Logistics, while the business justification for using a warehouse; the financial justification for owning or leasing and location decisions (the ‘why’) are within Supply Chains.

Both the ‘how’ and ‘why’ are valid and necessary learning and not an ‘either/or’ consideration. The question for employers and educators is the weighting given to each. A previous blog post outlines an approach to structuring cross-function supply chain education and training.

Employer actions: Many organisations use the terms supply chains and logistics (especially on the side of 3PL trucks), because they have become fashionable. But knowledge at senior levels about what these terms actually mean for their organisation is not so common. As an exercise, think about the following questions:

- Are you aware of manufacturing and/or distribution organisations which have changed from the traditional source, make and deliver vertical silo management model to a horizontal flow model for items, money, transactions and information?

- For the identified organisations, does the new model operate only within the organisation’s Core Supply Chains or does it extend to understanding the Extended Supply Chains – to actual end users and the originating farms and mines for materials?

- Do the organisations have a supply chain strategy, which incorporates the strategies for Procurement, Operations Planning and Logistics?

- Do the people responsible for Procurement, Operations Planning and Logistics work as a team (whether in a supply chain group or not)?

- Is the supply chain group responsible for the Sales and Operations Planning (S&OP) process, which has been successfully implemented?

There are likely to be only a few organisations which meet these criteria. Unfortunately, the lack of understanding concerning supply chain thinking develops its own scenarios, such as:

- If people are employed in departments (a vertical silo), with the expectation of that is where they belong (with only vertical promotion possible), then how do employees develop?

- A trend within companies in some countries and especially within logistics operations and at 3PLs has been the expansion of contract and casual employment and a reduction in the headcount of ‘permanent’ staff. What is the attraction of working for this type of organisation?

- An attitude among senior management that technologies are the solution to any challenge and that in the future people will be replaced in full or part by machines and algorithms. This ignores the dictum that ‘People add value and technology reduces costs’

- A reduction in training budgets leads to expectations that employees will fund their own training and education. The danger being that as employees ‘own’ the knowledge gained, it is easier for them to move to another organisation; increasing labour turnover

Retaining and growing talent in supply chains is a project for committed employers and education and training providers in each country. They have to ‘sell’ a vision to young people (and their influencers) and current employees that a career in supply chains is interesting, of value and rewarding.