Continuing disruptions

Ever since COVID19 appeared, there has been much comment in media channels about the need to have resilience within an economy, in organisations and through their supply chains. Recognising the challenge is a good start, but the need is to identify which step on the road to resilience should be the prime project.

It is now good policy for supply chains professionals to assume that disruptive events will continue. By September this year, there may be a shortage of diesel fuel in the Americas , which could delay the harvesting and export of grains. Also, over the next seven years, governments in many countries will be less able to incur additional debt, which could result in disruptions larger than currently experienced in Sri Lanka.

Resilience within a business

Resilience is defined as ‘the ability to deal with adversity, withstand shocks and adapt as disruptions arise over time’. More resilient ‘core’ supply chains (a business and its tier 1 suppliers and customers) can continue to function when exposed to major market, industry or supplier disruptions and adapt its business to assure continuity of operations.

Continuity can be difficult, as major disruptions can overlap and respond to other disruptions, so the timing, outcomes and consequences of the turbulence are often unknown. This is reflected in your supply chains, when customers and suppliers (and their customers and suppliers) in the network, respond to a crisis in different ways.

To have any hope of understanding your organisation’s supply chains network requires Supply Chains Network Mapping. This helps Logisticians to locate where in the Network there exists dependency by an organisation; or dependency on one region within a country; or a supplier deep in the network and where interdependencies between parties in the network exist. Also, where power is exercised between parties, that can influence a response to a disruption, such as providing an increased allocation of scarce materials.

The consulting firm McKinsey states that “in a crises, half the impact arises from the crisis itself, while the other half, good or bad, is determined by the response”. The response can be done under pressure to ‘do something’ with speed, which can result in unintended consequences. Alternatively, there can be a planning regime in place that is flexible in its design to answer multiple ‘what-if’ questions and where a planned response to disruptions are underpinned by knowledge of the potential consequences.

The prime project to address resilience in your business should therefore be a collaborative planning process methodology. The good news is that the methodology does not have to be developed, as Sales & Operations Planning (S&OP) is that planning process and it already exists.

As a tactical planning process, S&OP is designed for collaboration and agreement. The outputs can therefore carry authority. For example, although risk management in supply chains can be a defensive approach, S&OP can be the vehicle for better managing risk to improve the organisation’s growth prospects.

As supply chains gain more exposure in the popular and business media, the supply chains group in organisations can elevate their disciplines and use S&OP to achieve that. At the strategic level, the impact of management strategies, plans and decisions on the organisation’s supply chains and finances can be evaluated. S&OP can also provide tactical planning insights concerning when new products should be brought to market and which promotion activity should be run and when. This makes S&OP the ‘heart’ of the organisation, that can adapt quickly to changes and disruptions.

S&OP as the planning process

The challenge is that typically most businesses do not have an S&OP structure, nor much of the information required for forward planning. Also, few business that initially implement an S&OP process use an S&OP IT application, to assist in the collaborative planning between Sales and Operations. Therefore for many businesses, there is a need to have a ‘low-key’ implementation and work towards staged objectives.

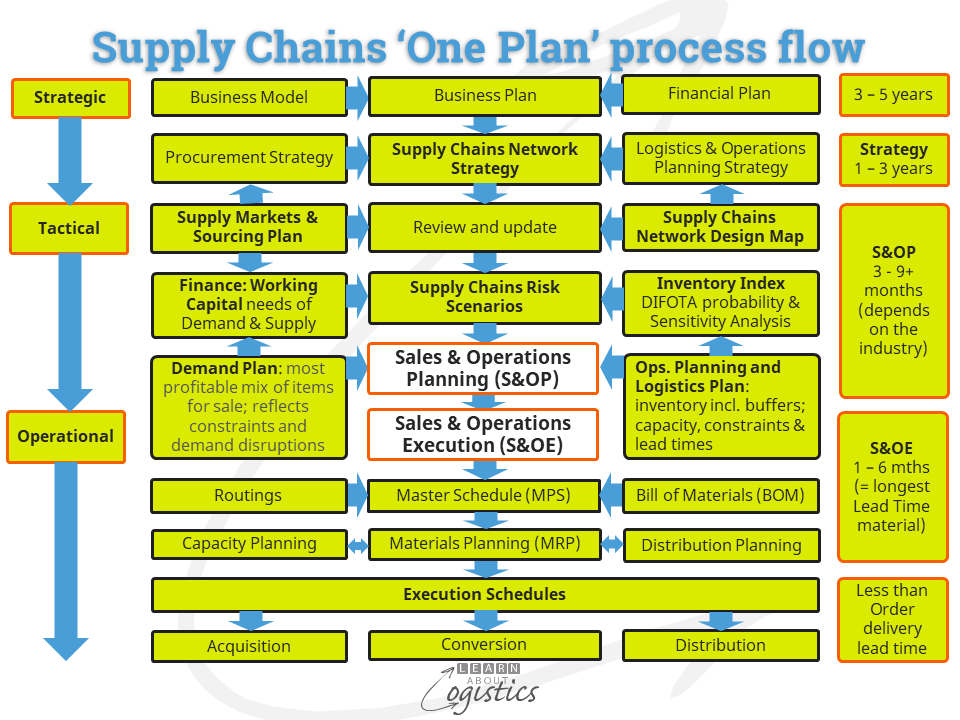

The diagram provides an overview of the ‘one plan’ approach to planning, whereby all planning and execution activities are linked and no department or group within a business needs to operate their ‘own’ plan. S&OP is shown as the ‘heart’ of the business, where the ‘Sales’ group negotiate outcomes with the ‘Operations’ group. The discussions are guided by inputs from Finance and use current information from other planning activities, all shown in bold.

While S&OP is not a software driven process, it requires accurate and timely input data to be effective for use in simulations and building scenarios. This will be discussed in the next blogpost.

For collaboration to become embedded in the organisation through using S&OP could take about three years, although some benefits can begin to show after about six months. The time is required to present an education process for affected staff, both current and replacement; revised processes to be implemented; new performance measurements (metrics) developed, used and understood and IT applications proposed, tested, purchased and implemented. It will takes time to change the culture in an organisation. The challenge will be a willingness to work at improving the process (and results) over this length of time.

To be really successful requires changes in attitudes about working collaboratively in teams and how ‘success’ is measured – S&OP is about achievable outcomes through collaboration.