Is there a ‘best’ structure for a Supply Chains group?

What organisation structure can work best for your Supply Chains group? Either a Centralised or Decentralised structure is the obvious approach, but do these consider the multiple functions in and supporting supply chains?

A Centralised supply chain model is best suited when the products generated from each business unit are similar (although markets may be dissimilar), and business units are geographically close. This enables similar planning, purchasing, storage and transport services. Under this model, the central supply chains group can make decisions and exercises control over relevant activities throughout the organisation. For example, Procurement can exercise Power over suppliers through leverage of the total corporate spend and implementing standard sourcing and purchasing processes.

A Decentralised supply chain model is best suited for organisations with divisions that operate as independent business entities, with limited sharing of information. In each business, there is a high degree of autonomy and control over Procurement, Operations Planning and Logistics policy and processes.

But are either satisfactory in the current business situation? A recent article by the US based research firm Gartner noted that “A Chief Supply Chain Officer (CSCOs) must deliver multi-value contributions where their investments create maximum impact across key priorities that include growth, resilience, sustainability, risk reduction, and other priorities, while also addressing cost. A focus on delivering multiple sources of value requires a rethink of organizational roles to support this objective. Gartner recommends that organizations consider which activities need to be integrated at the enterprise level and which should be differentiated at the business unit level”.

This is a valid argument, but also shows how understanding and implementing new or different approaches within the supply chains of organisations can take a long time. In the early 1990s, the approach now recommended by Gartner was actively promoted and implemented by the UK based Procurement consulting firm PMMS, under the acronym CLAN (Centre-Led Action Network), in companies with multiple SBUs (strategic business units) or divisions.

A Federal structure

The lead consultants at PMMS noted in their book Profitable Purchasing Strategies (Steele and Court 1996) that the CLAN concept could also be applied for Materials Management (which included at that time, Operations Planning and inventory management) and Logistics. Together with Procurement, this is today’s Supply Chains group.

The authors were at pains to emphasise that Centre-led is not an exercise in empire building. They identified that for a Centre-Led Procurement team, only 3-4 knowledgeable people were required. Therefore a Centre-led facility for a Supply Chains group in a multi-SBU business should be no more than 9-12 professionals.

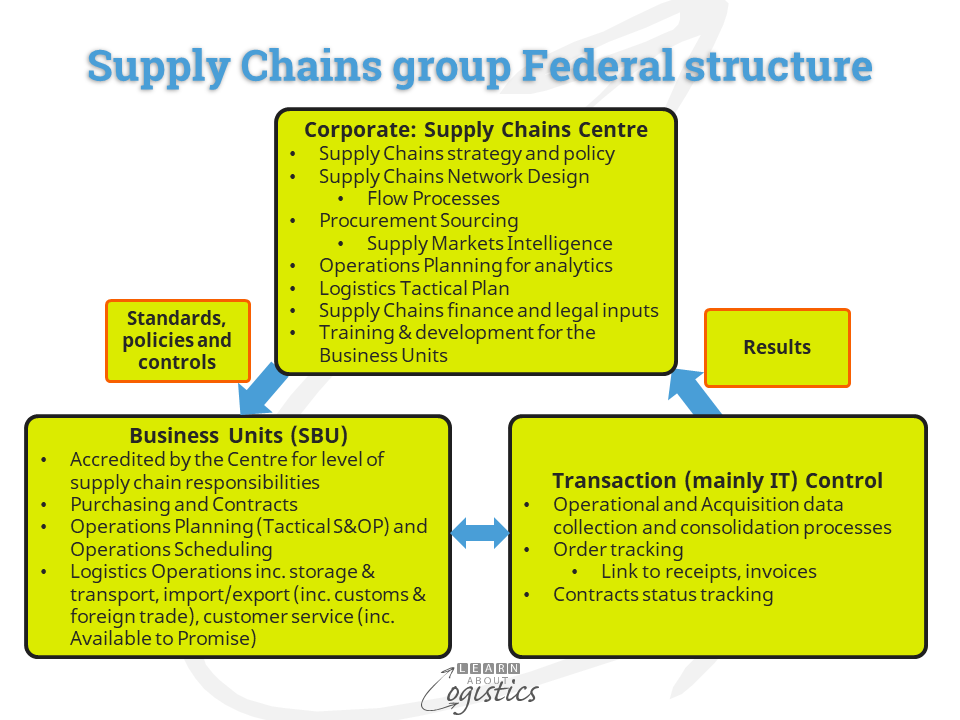

The Federal structure, shown in the diagram, is a ‘middle way’ when compared to Centralised or Decentralised structures. The Centre has its focus on strategy, strategic sourcing and corporate logistics and shares knowledge about ‘best practice’ and the organisation’s supply markets. The ‘doing’ (tactical planning and operational execution) is the responsibility of each strategic business units (SBU), but the Centre consolidates transaction data for analysis of supply chain performance. The Centre should lead initiatives for change with the SBUs and provide access to resources – applications, information and training.

Predictability in Supply Chains

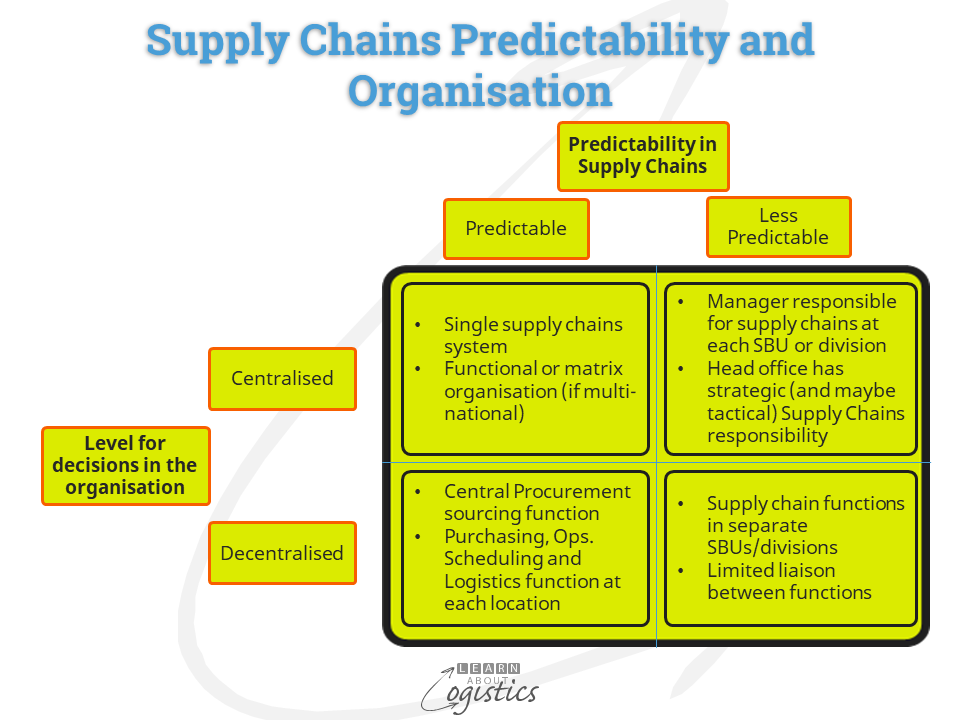

An adaptation of the Federal model has an organisation’s supply chains model based on product markets, marketing channels or major customers. This indicates that a factor to be considered in organisation design is the predictability within supply chains, governed by the sales and supply markets in which a business operates. The culture of the organisation also plays a part, which dictates the level of autonomy and influence allowed for business units. Also, the willingness (or otherwise) of senior management to mandate a policy or process that will apply across all SBUs in the business.

An example of using this matrix is a business with capital intensive infrastructure for the movement and storage of materials, such as from mines to loading ports. In this scenario, supply chains are more predictable, as the majority of ore could be sold on long-term contracts. The locations and operating decisions are likely to be decentralised. The supply chains organisation is therefore more likely to be structured functionally, with department efficiency and cost control as drivers.

Compare this with companies operating in the fast moving consumer goods (FMCG) and consumer packaged goods (CPG) sectors. Here there is less predictability, with decisions concerning supply chains made with reference to forecast sales and capacity at component suppliers, contract manufacturers, logistics service providers (including 3PLs), sea and air ports and retail outlets.

Responding quickly to changing retail customer requirements requires a focus on flows through the supply chains and managing processes rather than functions. Flows of items, money data and information respond to market and customer based objectives, such as ‘delivery in full, on time, with accuracy (DIFOTA). A processes is a sequences of activities that should create value for customers and in supply chains can happen through the activities of cross-functional teams. This requires tactical planning to be more integrated through the Sales & Operations Planning (S&OP) process, rather than in functional silos.

The supply chain organisation structure that is best for your enterprise will therefore depend on the business, industry and cultural setting. When customer markets, customers and business models change, so will supply chains. To match the supply chain structure to changing industry and business situations, senior management should ask the following questions:

- What decisions are critical within the organisation’s supply chains?

- Where in the supply chain organisation should these decisions be made?

- Do the people expected to make the decisions have sufficient authority?

The majority of tasks when establishing a different organisation structure for the Supply Chains group is about people and implementing change. And as that will involve multiple functions and discussions about collaboration, it will not be a short exercise that will also require ‘selling’ the proposal to the CEO.