Higher interest rates

The statement ‘We behave how we are measured’ is not only true of people, but markets and businesses. Low interest rates have not only fuelled high share (or stock) and real estate prices, they have influenced business behaviour.

For the past twelve years, low (or even negative) interest rates have encouraged some established businesses to borrow money for funding share buybacks, region or global expansion or and acquisitions. For start-ups, investors (venture capital (VC) funds, institutional investors and wealthy individuals) have taken the view that growing market share, using low (or ‘free’) prices, was more important for a business than being profitable – especially if the word ‘tech’ was used in the prospectus. So long as sales were increasing at very high rates, investors were willing to fund the growth in employees and costs. For example, a Sydney based home delivery grocery service (delivered in 10 minutes by electric bicycle) recently noted that each delivery lost $A13, but the number of customers was increasing, as was the order value. This situation can only continue if investors keep their purse open.

The hope by investors has been that a start-up business will eventually grow into another Amazon, with high market share in its sector, enabling some control or influence of a market and very high returns to investors. But with increasing interest rates, this period in the business cycle may have come to an end and a different approach is required.

Cash is again important

An old saying is that ‘Cash is fact, while profit is an opinion’. The money coming in and going out of a business is tracked using Cash Flow, which is difficult, although not impossible, to manipulate. As the cost of borrowing increases, companies will need to rely more on their own cash resources, so the measures concerned with cash will increase in importance. To measure the financial performance of an organisation’s supply chains, Working Capital and its derivative ‘Cash to Cash’ cycle is most likely to be the measure considered by senior management.

Working Capital is an applicable measure for the supply chains group (Procurement, Operations Planning and Logistics), because it is a measure of time – the essence of supply chains. The longer the process takes, the more money is consumed by the business. And, while the objective of supply chains is to provide Availability, items must be supplied within the most effective time frame. When Working Capital performance is deficient, it can indicate failings in the policies and processes of the supply chains group, such as the:

- lack of standardised business practices and processes

- lack of information sharing between parties in the supply chains

- customer credit management process

- customer invoicing process. Reduce invoice errors; improve response to overdue invoices; review the process for collecting money from customers and why accounts receivables age – address the customer service process concerning complaints

- management of inventory (policy, planning and performance). Review the balance between inventory location, form and function and only then take action to reduce or increase product line inventory as required

- planning of operations (logistics and production/imports). Review sales forecasting and the distribution fulfilment processes. Consider a make to order (MTO) or assemble to order (ATO) operations model, that enables a quicker collection of cash from customers

- sourcing and buying process

- relationships with suppliers

- suppliers’ invoice dispute resolution process

As a general rule, if 10 percent or more of accounts payables in a business take longer than 45 days to be paid, the business has a policy of using suppliers’ money to help fund the business. In a constrained cash environment, this is not a good policy for other parties in the supply chains.

The late receipts of payments made to a supplier affects their cash flow. If not able to secure the shortfall in funding, the typical solution is to extend payment terms to their suppliers. However, if a supplier at a lower tier in a supply chain provides critical items and becomes bankrupt, the effect can quickly reverberate through the supply chain; especially for those businesses operating in a ‘just in time’ (JIT) environment. As the Procurement function is responsible for managing business relationships with suppliers, the consequences, both immediate and longer term, of decisions about payments to suppliers need to be understood.

Cash to Cash cycle

Managing working capital and optimising operations of the core supply chains are two sides of the same coin. It is therefore preferable they be managed and measured within one entity – the supply chains group. The operating measure to use is the ‘Cash to Cash’ cycle, structured as:

- Inventory as days of supply plus

- Sales receivables in days outstanding minus

- Supplier payables in days outstanding

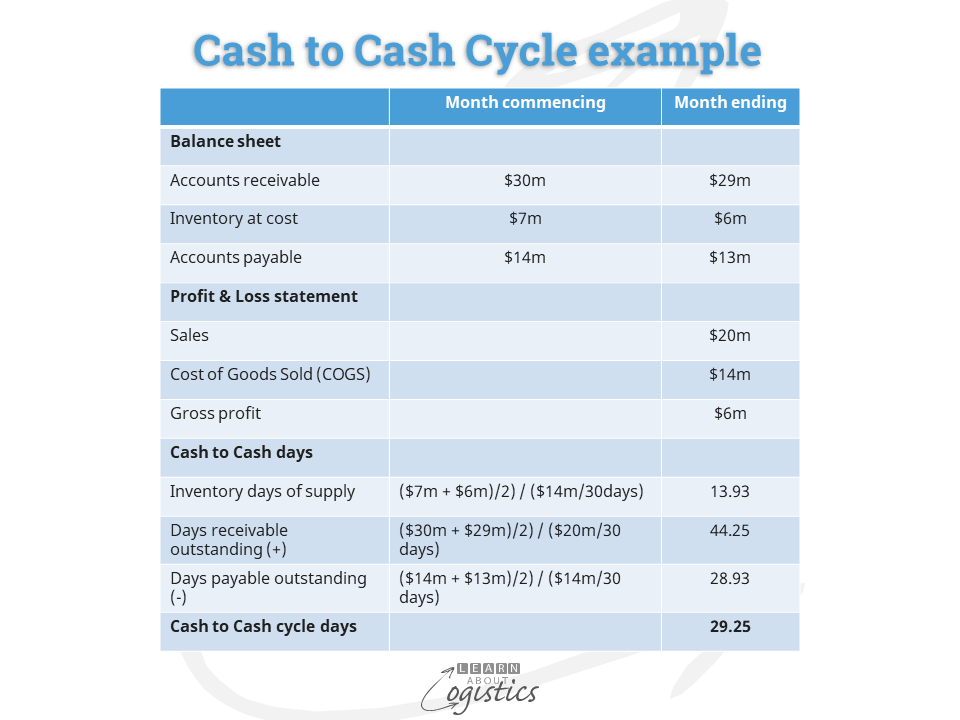

This measure identifies the time that cash is not available for use by the business. The calculation restructures the Working Capital formula to identify the time it takes for cash invested in inputs to flow back into the organisation, following the sale of products and services. An example of the calculation is:

However, it is preferable that ‘Supplier payables in days outstanding’ are added and not subtracted. The reason is because an order placed on a supplier becomes an obligation to pay. This approach can help to eliminate the temptation to extend payment time for suppliers.

Like most measures, ‘Cash to Cash’ cycle days results should not be viewed in isolation. Instead, review the trend of results and measure the standard deviation, to show whether the variability of results is ‘in control’. With a ‘Cash to Cash’ story to tell, supported by operating numbers, the supply chains group can work within their organisation and with customers and suppliers to identify requirements, policies and processes that could be changed and will have the greatest impact on Working Capital performance.

Projects can then be initiated to eliminate the impediments. However, try to avoid a focus on reducing time in more obvious, physical areas such as transport, which accounts for only a small part of the cycle. Instead, develop initiatives, such as information sharing between parties in the supply chains, that require the co-operation of multiple people and organisations.