Legislation for supply chains

It was only a matter of time before individual countries enacted laws and regulations to formalise the obligations of financial firms concerning ESG (Environment, Social and Governance) targets. This action would be followed by the requirement for product companies to report on the ESG of their supply chains. It has now happened

The German legislation, titled the Supply Chain Due Diligence Act (SCDDA), will be effective from 2023 and initially apply to domestic and international companies registered in Germany, with more than 3,000 employees (1,000 from 2024). Under the SCDDA, companies will be required to exercise due diligence in their supply chains (own operations, direct suppliers and indirect suppliers) in accordance with environmental, human rights and governance requirements.

The SCDDA will oblige companies to :establish a risk management system to analyse environment related risks, human rights and governance; adopt a policy statement and appoint an in‑house responsible person. Companies must prepare an annual report on the performance of their obligations, which must be available on the company’s website no later than four months after the end of the business year. There will be penalties for non-compliance.

Also, the European Commission is preparing a legislative proposal to be presented in Q4 2021. The Directive, will require that companies put into place a due diligence process to “monitor, identify, address and remedy risks to the environment, human rights (social) and governance (ESG) in their operations and business relationships”, for example:

- Risks related to the environment would include operations that contribute to climate change or other environmental damage

- Risks to human rights would include the potential or actual breaching of labour law conventions

- Risks to governance cover corrupt practices such as bribery

The Directive will apply to all businesses in the EU and also to companies outside the EU that operate in the EU by selling their goods or providing services within the EU. Compliance will therefore be required by the supply chains of all entities with business connected to the EU.

Addressing the legislation

Both pieces of legislation will influence the supply chains of many large and medium size international businesses and their tier 1 suppliers. Contracts with tier 1 suppliers will need to contain clauses relating to compliance with the legislation. In turn, the tier 1 suppliers are likely to require their tier 1 suppliers to comply, or risk losing the contract. This will not occur overnight, but the intention is for a more inclusive approach to ESG improvements through supply chains by 2030.

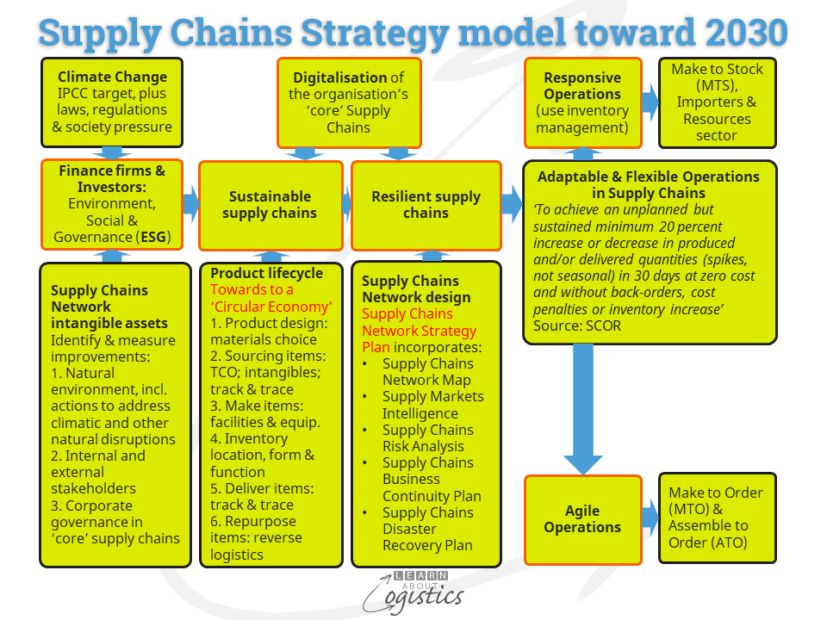

The more formal, legislative structure for ESG shows that it is not a ‘fad’ that will go away. Therefore, supply chain professionals need to give serious consideration about the structure required to ‘monitor, identify, address and remedy’ ESG risks in their supply chains. The proposed model for Resilient supply chains that was discussed in the previous blogpost can be used for addressing ESG requirements. It consists of five documents, shown in the block ‘Supply Chains Network design’ in the diagram below.

Your organisation’s Supply Chains Network Strategy Plan is informed, then enabled by knowledge of the supply chains. This ‘knowledge bank’ is contained in the Supply Chains Network Design Map. The activity commences with locating operational facilities within the Network:

- Nodes: at each location in the Network which holds material, items or money. The maximum details are for tier 1 suppliers and customers manufacturing and warehouse locations. Lesser details are collected for entities further upstream and downstream.

- Variables – factors that can change the physical or financial values of items and money at a Node

- Value Added Nodes through each Supply Chain

- Customer demand patterns through each outbound Supply Chain

- Capacity and responsiveness at Nodes

- Flows of: items, money, transactions data and information at Nodes

- Weak links in each Supply Chain, identifying:

- redundant Nodes and Links

- benefits and costs of alternatives

- Links: the connection of two Nodes by a transport mode movement of materials and items. Note potential bottlenecks and wait times at country borders. Identify Logistics Service Suppliers (LSPs) that own, control or influence critical links

Inputs to the Supply Chains Network Design Map are: Vulnerability of the business to sources of risk that may affect countries, populations and industries; knowledge of end user markets provided by Marketing; Supply Markets Intelligence (SMI) and Risk Analysis at Nodes in the supply chains.

Supply Markets Intelligence is the process of identifying the capability of each supplier and their supply markets, including identifying the extent of power or dependency by suppliers in the particular market. The analysis of a supply market can assist establishing the risk profile and sourcing decisions through identifying:

- Constraints and potential threats related to a material or item, including trade influencing actions undertaken by governments

- The influence of financial markets, exchange rates and price trends on final product costs

- Security of supply issues, including conflict materials

- Potential alternative sources of supply

- Technology developments, including potential alternative materials

The categories of Vulnerabilities to the business are:

- Environmental:

- Natural physical hazard risks that may be insured e.g. earthquakes, volcanoes

- Climate risks e.g. droughts, forest fires, storms (cyclones, typhoons and hurricanes) etc. that can be attributed to climate change. Insurance companies can be reluctant to cover these risks, as they are influenced by human activity

- Economic

- Geopolitical actions

- Infrastructure related disruptions, such as IT systems, transport networks (including ports) and utilities (power and water)

- Social includes long-term social unrest; labour shortages due to demographics (an ageing population), population relocation due to unrest or climate change and expected pandemics

Categories concerning External Risks at Nodes and Links are the same as the previous list, but apply to the organisation’s supply chains rather than country economies. In addition to the External Risks, the analysis considers:

- Supply Chain Risks attributable to the respective inbound and outbound supply chains;

- Internal (enterprise) Risks that are related to potential disruptions in the execution of an organisation’s supply chain strategy and operations

- Supply Chain Process Risks identify an inability to achieve consistent outcomes relating to the sourcing and operations planning of items and resources and the delivery of products or services

Risks identified that may occur within a relatively short time span could affect business viability. They are placed under the heading of supply chains Business Continuity for input to the Continuity Plan and Disaster Recovery Plan. These provide for the Response and Recovery phases of disruptions to supply chains.