Your supply chains may change

Supply Chains is a term that at last has entered daily use, but it has taken a global emergency for that to happen. The question for supply chain professionals is whether your supply chains and logistics will need to change when commerce returns to ‘normal’, whenever that will be?

When business is in a growth mode, competitive pressures allow, with minimal analysis, the introduction of new products, trade routes, warehouses and sales outlets. So, when serious disruptions occur, it offers a ‘window of opportunity’ for enterprises to review their business model and for governments to review policies and regulations.

Availability of goods

Inventory that was in place prior to the Lunar New Year holiday has enabled businesses to supply their customers. However, supply chains have been inconvenienced over the past two months as airlines cancel flights on many routes (affecting freight as well as passengers), container shipping routes and volumes are disrupted and delivery of imported goods to the home has lost its sense of urgency for consumers.

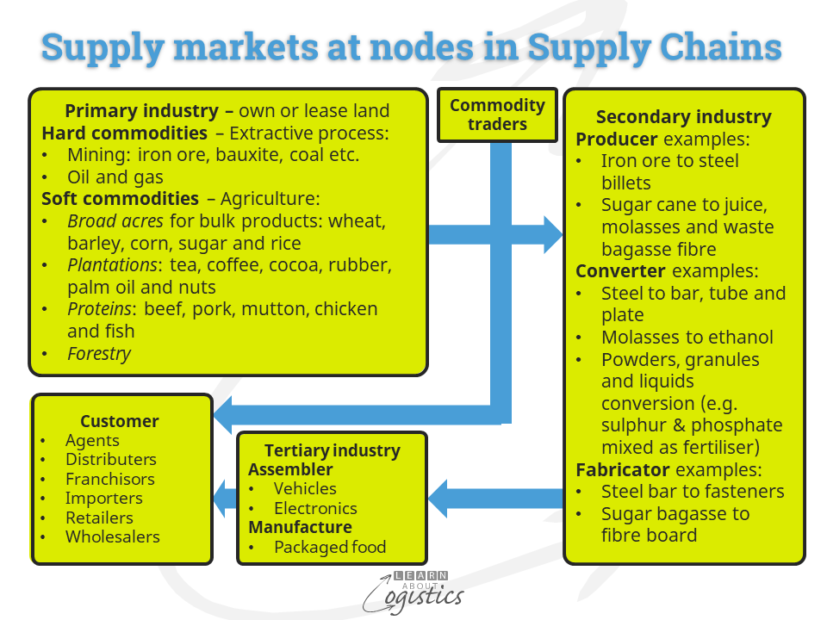

The end of March has been identified by some senior executives and commentators as the time for supply chain disruptions to become very apparent. As major highways start to re-open and truck movements return to near usual levels in China, bottlenecks at factories and ports will become evident, as the nodes of supply chains are out of balance.

The illustration indicates that challenges start at the raw materials level. For example, steel mills in China have been producing, but since late January have held the finished billets in inventory. If converters cannot accept the billets at an acceptable rate (maybe due to working through older inventory), the steel mills will need to slow production, which affects deliveries of imported iron ore.

Assemblers and manufacturers throughout the Asia region are interdependent for ‘intermediate goods’ (parts, components and sub-assemblies). So, disruptions at converters and fabricators in China and in other countries of Asia and beyond, will affect deliveries to end users by assemblers and manufacturers.

A possible lack of products could reduce throughput at seaports, container shipping capacity and delivery transport in customer countries. This will affect both consumer and industrial supply chains, such as inputs for the construction and fit-out of apartment and office buildings.

Possible changes for consideration

Among the immediate challenges is the experience in China of people switching to on-line ordering of grocery items. In late January and early February, the number of orders processed at automated warehouses of JD Logistics in Wuhan, China were reported to increase from an average of 600,000 to 1 million per day.

This experience is likely to be replicated, as other cities and countries experience increasing infection levels. The question is whether these customers will return to visiting physical shops when the virus subsides and if not, how will extra deliveries be processed?

To address the many challenges of increasing ‘last mile’ deliveries, cities are enacting changes. In London, there is an estimated 400 million deliveries per year of goods to personal addresses and in Amsterdam there are about 25,000 delivery vans which drive daily within the city’s ring road.

The plan for Amsterdam is that from 2025 only zero emission vehicles will be allowed inside the A10 ring road. This will require the building of cross-dock facilities around the city perimeter, where large trucks will unload; items are sorted for delivery and loaded to smaller electric vehicles.

The trials may also result in imposed delivery solutions, including consolidated deliveries to defined areas, ‘time of day’ delivery periods and road usage charges (that may curtail ‘free’ deliveries). These approaches could be brought forward, based on the evidence obtained from the current disruptions.

Organisations are being urged by governments to assist their staff to work from home (and finding it easier to do than they thought). Also, for business meetings, teleconferencing is at last replacing airline trips and overnight hotel bookings. If implemented permanently, these changes will affect the passenger transport and hospitality sectors.

Concurrently and not surprisingly, the consumption of oil products has decreased, providing a substantial reduction in pollution levels for some cities. This provides an opportunity to bring forward urban planning policies concerning the movement of freight.

A risk is that supply shortages translate into a reduction in demand for discretionary items, which could become permanent. The reduced revenues currently experienced among businesses along the supply chains (and lost income by employees, who are consumers) will focus boards of directors and senior management on the business model. Maintaining cash flow to survive the current disruption and planning for the future, will require reviews of alternative supply chains and alternative modes of transport.

Response to changes in supply chains

Research by Supply Chain Insights indicates that recovery of supply chains from major disruptions takes an average of 6 months and for many companies up to 15 months. The extent and severity of the current disruption is likely to mean that alignment of supply chains will take longer to achieve.

For businesses making and selling goods, risks to business continuity may include too much reliance by Procurement on sole suppliers or single countries. A review about policy should consider whether:

- Multiple suppliers are required for critical items and

- Critical items are produced at multiple sites within a region or country

There are also two processes that should be reviewed for their viability, given the added risks:

- Outsourcing of business functions – an idea that appears to have been accepted as a ‘good’ business practice; But, some businesses may have progressed this initiative without a total cost analysis

- Contract manufacturing, often in what are called low cost countries (LCC). The cost savings from manufacturing labour in low cost countries have reduced, requiring an ongoing total cost of ownership (TCO) analysis

The current challenges for supply chains will likely accelerate (although slowly) a move of manufacturing closer to consumers in a country or region where the products are sold. The move will be aided by new technologies, as they are accepted and adopted as the implementation challenges are overcome.

As this discussion has indicated, changes to your organisation’s supply chains will be an outcome from the current disruptions. The challenges will be time to undertake the review, assigning sufficient resources and planning the implementation of changes.