Algorithms and us.

In our everyday lives, computers control the activities of infrastructure such as traffic lights or energy availability and we trust that the outcomes are the best available under the circumstances. This is accentuated with social media able to advise the ‘best’ restaurant, movie or book for us, based on previous selections and those of our ‘friends’. These interfaces with computer generated directions, answers and recommendations builds a level of trust (or distrust) in the solutions.

Algorithms are the means by which computers generate solutions. In common use today, the term was not identified in a dictionary published in 1970. There are a number of definitions available, which all refer to at least “a set of instructions, process or set of rules performed in a prescribed sequence to achieve a certain goal”. Not all definitions mention a computer, but it is likely to be assumed. While computer based algorithms are not expected to be biased, the people who write them most certainly can be, yet generally users do not know (nor care) how the algorithms which provided their instructions or recommendations are constructed.

The discussion about consumers ‘right to know’ is for another place. But in the situation of managing commercial undertakings, there is a need to know. The increase in available data means that more use will be made of algorithms to interpret the data into a form that provides input for decisions – or even make the decision!

This latter situation was illustrated this week when consumer brand companies, advertising firms and government departments in the UK and France withdrew digital media advertising from major social media sites. The traditional media advertising process for placing advertisements has been largely replaced by computerised, or programmatic, advertising systems. This means that advertisers have no control over where their advertisements are placed, nor accountability in measuring the effectiveness of advertisements across global digital media.

The situation is that algorithms (or more accurately, the programmers that wrote them) have decided it is acceptable to place advertisements for major consumer products or government information alongside extremist content. Obviously, brands and governments can suffer significant reputation damage from being associated with this type of material.

Here, marketing and advertising executives had trust that algorithms designed and written within social media companies and promoted by those companies would meet some undefined criteria of acceptable placement. Whereas, the social media companies are only driven by advertising space sales quotas (and the linked bonus).

Algorithms and supply chains

When it comes to your supply network, the talk about ‘intelligent’ supply chains should trigger some concern about two factors; the accuracy of input data and assumptions made in developing the algorithms. Input data obtained directly from making and packing equipment should be reliable. However, in supply chains there are data layers between an item in its immediate protective wrapping and movements of loaded containers and vehicles.

At each layer, master data (the descriptor of the item) and the transaction data must be transmitted to and reconciled at the next level or node in a chain. When a party receives updates for an SKU concerning the item, location and supply or demand, organisations with a need to know should receive the same data update direct to their databases for:

- sales and merchandise documents

- inbound and outbound item movements

- invoice reconciliation and payments

However, my book stated that the standards organisation GS1 found the UK grocery retail sector had over 80 percent of transactions between suppliers and retailers with inconsistencies, in what should have been identical data. In the US, more than 60 percent of attribute values about new and changed products required correction, more than 30 percent of traded items (cases and pallets) and more than 50 percent of consumer end items contained incorrect data.

In ERP systems, the product master data structure is based on the application designer’s definitions. Master data entry of the same product is generally allowed multiple times, using different product descriptions. So, there are many places for errors to enter the data, with algorithms able to accept and use, maybe without any validation process. More than 30 years ago, APICS presented training classes on ‘achieving data accuracy’; since then I have not noticed a greater focus in businesses on improvements to this area.

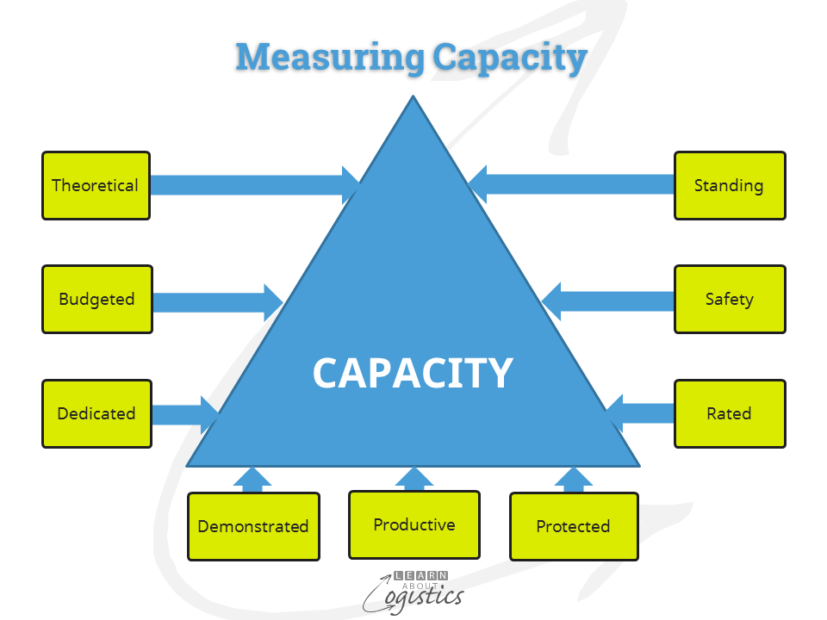

When developing supply chain algorithms, the assumptions can contain many areas for disagreement. As an example, capacity is used as input into the Sales & Operations Plan (S&OP) to balance demand and supply. However, capacity is under constant change, due to the product mix, process and equipment improvements and transport mode availability; that is flexibility of an operation. As shown in the diagram, there are nine ways to measure capacity and each is valid – what criteria will the algorithm designer use to structure each type of capacity?

With the pundits telling us that supply chains (and therefore the core functions of procurement, operations planning and logistics) will become more automated, there will be an increasing reliance on algorithms with outputs that we, as supply chain professionals, are expected to trust. But without knowing how an algorithm validates inputs and defines the assumptions used, we maybe taking trust to the level of advertising executives – without control of their brand reputation.