Waste in Supply Chains.

The United Nations (UN) has an objective that by 2030, global food waste will be reduced by 50 percent. This is an ambitious goal, which not only requires leadership by governments, but active involvement by supply chain professionals – those that view Logistics as more than ‘box shifting’.

Food waste in the agricultural supply chains of developing economies is a major challenge – more than 40 percent of grown produce is lost before final sale. This is due to poor logistics practices through the supply chain, excessive exposure to the elements after harvest and a lack of cold storage infrastructure. The situation could be considered as a problem specific to developing countries; but there is also a ‘farm to fork’ challenge in developed countries, but for different reasons.

In developed countries, major retail chains that exercise power in their relations with suppliers, demand ‘blemish free’ fruit, vegetables and horticulture products at each stage through a supply chain – in the field, packing shed and distribution. The outcome is that, depending on weather conditions, at least 25 percent of all fruit and vegetables in developed countries are unlikely to conform to retailer’s specifications. This results in substantial waste, with food diverted to cattle feed or destroyed, but also a waste of land and inputs plus transport and handling costs.

When my wife and I were growing raspberries for fresh sale (a good sideline to consulting), the processing of second quality fruit was of equal importance to profitability as the top quality products; the production of frozen, jam base and puree were critical. Likewise, steps have been taken to turn other blemished, but edible, items into convenience products for sale. But this is generally at the initiative of individual farmers, rather than an industry or government lead strategy.

Using more of the food grown is required because indications are that multi-millions of additional consumers will enter ‘middle class’ status by 2030 – and the current utilisation rate of soft (agriculture) and hard (minerals) resources will not be sufficient to satisfy that group. With this realisation and building on the experiences of Reverse Logistics, there are developments to recognise the reuse of materials and ‘food miles’ (the distance a food item has to travel and energy consumed) as being an integral and necessary part of supply chains.

The overall term for these factors is Sustainability. This is a strategic business issue, beyond maintaining the viability of the business and is driven by government legislation, consumer concerns and employee opinion. Sustainability is underpinned by risk – what level of risk (and therefore added cost) will your organisation accept of a current situation before it changes its behaviour (culture and strategy) to reduce the vulnerability of its supply chains?

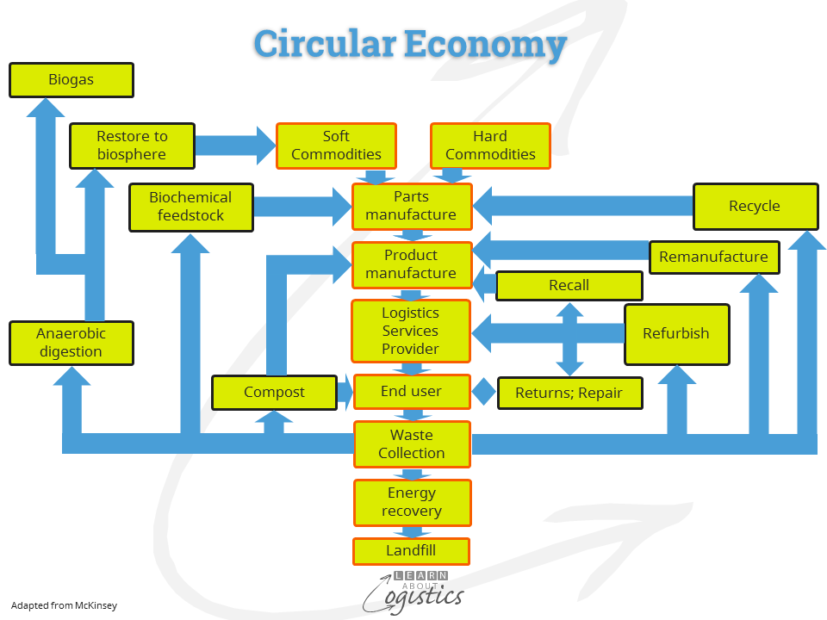

For many businesses, Reverse Logistics will become an integral part of Environmental Logistics, which has the aim to reduce all Sustainability-based logistics costs. Reverse Logistics is “activities required to retrieve a ‘dead on arrival’ (DOA) or used product from a customer or consumer and either reuse or dispose” as it goes back through a supply chain. Attention to date has mainly focused on discrete manufactured products, but it can be applied to all items. The activities commence with ‘re’:

- recall (faulty product)

- repair (service to a product)

- returns (warranty claim)

- recycle (convert to another item)

- refurbishment (restore the condition of a product at the end of lease or rental period)

- re-manufacturing (overhaul a product when it has achieved a set number of operating hours or at the time of trade-in)

Refurbishment and re-manufacturing are making products good for reuse and therefore they will re-enter the sales channels. This activity is called re-marketing. Reverse Logistics can also apply in service based logistics, for example returnable plastic baskets on pallets for distribution to supermarkets by agricultural suppliers.

New thinking – Circular Economy

When applying a Sustainability view to your organisation, an approach is to replace the current ‘take, make and dispose’ with ‘restore’ – that is to design for reuse, or multiple cycles of disassembly. This concept will be aided over time by growth in the renting economy, with its emphasis on handing back at a prescribed time. The process is called the Circular Economy by the consulting firm McKinsey and is shown in the diagram, applying the ‘re’ terms:

A supply chain is designed and built around ‘progressive dis-aggregation’; that is, as materials progress through the inbound chain and then products through the outbound chain, the parcel size is progressively reduced. However, the reverse logistics process does the opposite, with many additional steps to process the reuse of an item. Following assessment, the additional steps for items assessed for refurbishment and re-manufacturing include additional ‘re’ activities of repackaging, relabelling, restocking and reselling, which can result in the total cost of reverse logistics being substantially more than forward logistics.

This makes the Circular Economy (or any later term used), a ‘here and now’ challenge for Logisticians. However, it appears that unless there is government legislation or industry sector leadership, enterprises are generally not forthcoming in establishing a Sustainability and Reverse Logistics culture, because the concept is considered only as a cost to the organisation.

Sustainability and Reverse Logistics is currently a ‘poor cousin’ in business – a process that often does not have an owner, is not allocated resources and not professionally managed as expected expect of outbound logistics. While we can get excited about the possibilities of drones and automated vehicles, operating within a Sustainable environment at lowest total cost will be a much bigger challenge for Supply Chain professionals over the coming years.