Working within complex systems.

Supply chain planners should be able to access more than transaction data from company IT systems. There is streaming data from instruments and unstructured data from the Internet. These are in increasing amounts; but can your current ERP system turn this additional data into information that is of value to planners?

The selection and implementation of ERP systems is an expensive, even traumatic, experience; therefore the replacement cycle can be more than ten years. However, the pace of change in business models and information technology is exerting pressure on businesses to update the way information is accessed, managed and used. All too often, discussions about IT applications is focussed on features and benefits; but, the place to start the discussion is business objectives. What do we want the business to achieve and how can IT applications assist?

For brand companies and shippers, about 70 percent of all data transacted in the business is connected with the company’s supply network; for Logistics Service Providers (LSPs) it will be close to 100 percent. But supply networks are not static in their structure – they are complex, adaptive systems (CAS). Therefore, management should recognise that systems which should respond to external events must be flexible in structure. Your business also needs to recognise the potential for some of the following events to occur:

- With the high and increasing level of outsourcing, data should be viewed and used from a network planning perspective, rather than the traditional single enterprise resources planning (ERP) system

- If your business is in growth mode and there has been acquisitions, is there more than one ERP system?

- Growth can mean expansion into smaller markets that are unable to justify a full feature ERP system, so a different approach is required

- Discrete product businesses are restructuring, wherever possible, to become engineer to order (ETO), assemble to order (ATO) or make to order (MTO) businesses; these to be more agile in response to customer requirements

- Government legislation concerning data privacy and the dissemination of data across borders can affect timely access to data

Each of these scenarios requires a different approach to the planning and scheduling process; however, the fundamentals do not change. Consider the data transaction points within a supply chain:

- link with transport schedules and book space on ships, trains or aircraft

- book road truck or space on a truck

- pay freight invoices

- arrange financing of shipments – import or export

- track movement of goods on transport modes

- link to customs and customs brokers – pay import duties

- link to insurance companies – pay premiums

- register delivery or receipt of shipments

- notify supplier of non-conformance of a shipment

- receive notification of non-conformance of a delivery

- pay for received items and collect money from customers

- track items in warehouse

- locate and count inventory

At each of these transaction points, the accounting system is informed concerning sales, orders, shipments, receipts, collections and payments; together with changes in the status of goods. At the same time, the data is required by planning and scheduling specialists for their work tasks. The planning and scheduling applications are often contained within an ‘integrated’ ERP system, because that is considered an effective way to manage data and information. But, while these applications are acceptable, they often contain structural compromises, which more focussed applications will address.

Another look at ERP systems

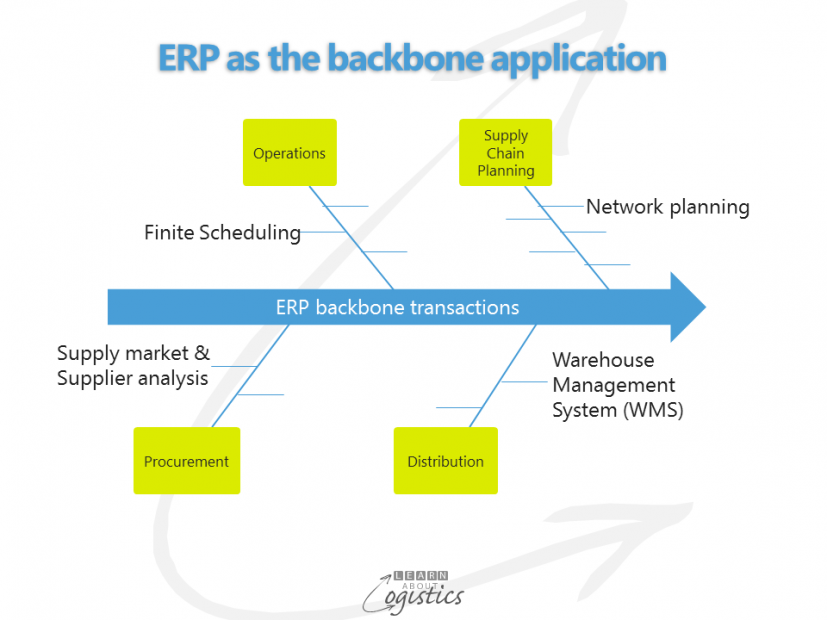

As I note in my book A Framework for Supply Chains, the pressures on businesses, outsourcing activities, rigidities within ERP systems and increasing streaming and unstructured data means that a re-look at the role of ERP systems is required. Instead of a comprehensive ERP system, with its fixed functionality, your system structure could have an ERP application act as the transaction backbone for the business, containing an audit trail of all transactions, plus accounting, operations control and HR records. ERP would interface with specialist supply network analysis and planning (SNAP) applications, plus applications that serve other parts of the organisation, to supply base data from the transactions.

The diagram identifies disciplines with an organisation’s supply chains and an example of a specialist SNAP applications used by each discipline. Within this scenario, the SNAP applications, whether based in-house, at a data centre (i.e. cloud) or at a LSP, will access base data from access points along the backbone, convert the data to information, then use it to complete analysis, planning or scheduling tasks; finally send the solutions to the ERP application for consolidation.

The difference between the two approaches from an IT perspective is:

- The ‘integrated’ approach uses the ERP database, therefore data synchronisation occurs within the database

- The ‘interfaced’ SNAP applications are likely to maintain their own data structure and need to synchronise with the ERP backbone database

The trade-off is that the SNAP approach may have functionality that better suits your business, but it is likely to cost more to maintain than an ‘integrated’ ERP approach. If your supply chain group consider the use of SNAP applications is preferable, then you must build a substantial argument to support the case, because finance and IT will most likely support the lowest cost and less challenging scenario.