Inventory is a cost or asset.

Too often, inventory is viewed as just a feature within a business – that is, until it is the cause of lost sales. I always hope that understanding by senior management will improve about the value of inventory and the people who manage it, but there is still a way to go. Two situations this week illustrate the situation.

The first concerns a media story about a major retailer in Australia. As part of a software upgrade, a new stock management system was implemented in March to make it cheaper and easier to source products. However, orders for new stock did not happen and the retailer’s shelves became emptier. This hurt sales – same store sales dropped by more than seven percent. It also hurt their suppliers; unable to supply due to lack of orders, but also affecting their business planning and orders placed on their suppliers and so on, rippling through the supply chains.

The background to this story was not provided, but it illustrates that managing inventory remains a critical part of business. Inventory is items that have been purchased but not yet sold, whether held in stock or just in time.

The second situation was my visit to the local pharmacy (drug store) to buy an over the counter (OTC) health product. It was not on the shelf and the sales person told me it would be two weeks before replacement stock would be received. The manufacturer only accepts orders on a monthly basis from this pharmacy and apparently delivers from their central warehouse, 800 km away. This is not standard practice, as I was told that competitors send replacement stock within two days.

It is likely that the brand company views its customers in the traditional manner of segmenting customers by size and type of retailer. This could result in :

- large retailers: large orders serviced with full pallet loads;

- independent retailers, smaller order sizes serviced with (say) half pallet loads

- small retailers in city and suburban shopping centres and streets: small order serviced with shippers/cartons

The cost to serve each of these segments will increase. Therefore, small retailers could pay higher prices or, in this case, receive a lower level of service. The manufacturer may have considered the policy correct for their business, but there were three outcomes from my visit:

- the manufacturer lost a sale

- as the sales staff are pleasant, the pharmacy did not lose a sale

- I decided to try a competitor product

Know the Cost to Serve your customers

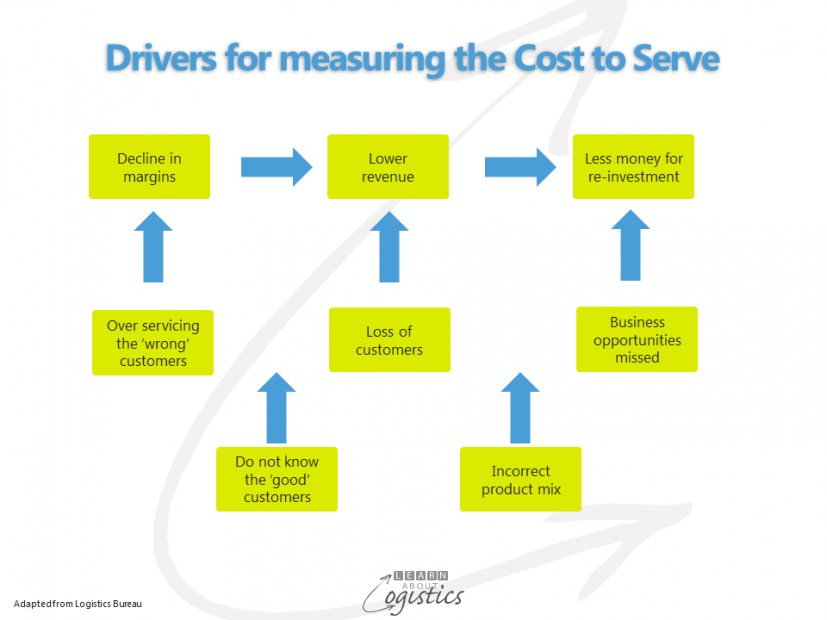

To minimise the risk of losing consumers and to improve the profitability of its business, this health care business (and any business) should know the Cost to Serve (CTS) their customers. The diagram illustrates why CTS is important – if you do not know the true cost, how can you manage?

The CTS analysis provides information about the actual cost of servicing individual customers, by identifying and quantifying the business activities involved. Under traditional accounting methods, the profitability of a customer is calculated by subtracting the cost of goods sold (COGS) from the net sales value. But the outcome provides little information for decision making by logisticians, as it hides the multiplicity of costs incurred in actually serving the customer.

The gross margin by each customer will differ, even if the products sold are similar, as there can be differences in the CTS for each customer. Your business may assume that customers with good volumes and profit margin are ‘major accounts’ when the accumulation of actual costs means that some ‘good’ customers do not return a profit.

There are multiple cost elements within the process of delivering goods and services to be considered for each customer. Some examples of cost elements are:

- Pre-sales costs: sales calls; request for quotations

- Selling costs: key account management time; order processing costs

- Storage and handling costs: dedicated inventory holding costs: dedicated warehouse space; material handling costs (special handling); non-standard packaging

- Delivery costs: delivery distance and traffic congestion time; location and access time limitations

- After-sales costs: returns (due to change in customer requirements); refusal due to late arrival at customer DC; trade credit (actual payment period)

- Retail specific customer costs: promotional costs (in-store and co-operative); merchandising

The analysis provides the basis for action to improve the profitability of low and negative profit margin customers and thus improve viability of the business. CTS can also be used to identify the real costs of serving particular markets and seasons.

Examples of actions that a business may take as a result of CTS analysis are:

- Restructure distribution channels

- Review the locations of inventory

- Compare costs between distribution facilities and sales regions

- Review logistics service provider (LSP) contracts and clauses concerning delivery responsibilities

- Renegotiate agreements/contracts with the customer

- Review the pricing structure of products and services

- Review the payment terms, discount policy and early payment discount structure

In the case of my local pharmacy, a CTS analysis would identify the true cost of serving the shop. If margins were not satisfactory, one possible solution to maintaining shelf space at small retailers would be to contract with a ‘route trade’ distributor, rather than making direct delivery from the factory warehouse.

The challenge with CTS is that while the principles and outcomes are evident, the continuing collection, entering, interpretation and analysis of data can be a large task. Implementing CTS therefore requires a funded project supported by senior management, with a design structured for ease of use and implemented as an organisation wide effort, not just a logistics exercise.